DOI: 10.20986/resed.2021.3851/2020

ARTÍCULO

MECANISMOS ETIOPATOGÉNICOS DE LA ARTROSIS

ETHIOPATHOGENIC MECHANISM OF OSTEOARTHRITIS

A. Oteo Álvaro1

1Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid, España

ABSTRACT

Osteoarthritis is an incurable disease characterized by a progressive deterioration of the articular cartilage associated with a subchondral and osteophyte bone proliferation, which causes pain, limitation of mobility, disability, and deterioration of the patient's quality of life. There is a clinical discrepancy between patients who are radiologically in a similar stage.

A series of risk factors have been described that would act systemically or locally in each joint. These factors alone or coincidentally would give rise to structural alterations of the joint tissues and would develop the disease. The actual mechanism by which these risk factors act is not entirely known. Knowing their way of acting and when they act would be a good opportunity to carry out a specific and early treatment that prevents the appearance or progression of osteoarthritis.

Key words: Osteoarthritis, histological changes, pathophysiology, risk factors, knee, hip, hand

RESUMEN

La artrosis es una enfermedad incurable que se caracteriza por un deterioro progresivo del cartílago articular asociado a una proliferación ósea subcondral y osteofitaria, que provoca dolor, limitación de la movilidad, discapacidad y deterioro de la calidad de vida del paciente. Existe una discrepancia clínica entre pacientes que radiológicamente están en un estadio similar.

Se han descrito una serie de factores de riesgo que actuarían de forma sistémica o local en cada articulación. Estos factores, solos o de manera coincidente, darían lugar a las alteraciones estructurales de los tejidos articulares y desarrollarían la enfermedad. El mecanismo real por el cual estos factores de riesgo actúan no es del todo conocido. El conocimiento de su forma de actuar y el momento en que actúan sería una buena oportunidad para realizar un tratamiento específico y precoz que evite la aparición o la progresión de la artrosis.

Palabras clave: Artrosis, cambios histológicos, fisiopatología, factores de riesgo, rodilla, cadera, mano

Correspondencia: Ángel Oteo Álvaro

angel_oteo@telefonica.net

INTRODUCCIÓN

La artrosis es la enfermedad articular más frecuente, que generalmente se desarrolla en personas mayores de 50 años (1). Es causa frecuente de dolor, rigidez articular, crepitación o ruidos articulares, limitación de la movilidad, en ocasiones de derrame articular con mayor o menor grado de inflamación y de un deterioro progresivo de la calidad de vida (1,2). La enfermedad se caracteriza por una progresiva degeneración y pérdida del cartílago articular, una proliferación osteocartilaginosa subcondral y de los márgenes articulares, condicionando un estrechamiento del espacio articular y dando lugar a la formación de osteofitos (3). Los síntomas más frecuentes son dolor articular, rigidez, ruidos y crepitación, alteraciones sensitivas, limitación de la movilidad y en ocasiones derrame articular y un mayor o menor grado de inflamación (2). Estos síntomas pueden ocurrir en cualquier articulación, aunque las localizaciones más frecuentes son la rodilla, la cadera y las manos (4). La presencia y la intensidad de los síntomas es muy variable entre pacientes con el mismo grado de alteración estructural (4,5), lo que podría ser consecuencia de la presencia, o no, de una serie de factores de riesgo y del estado psicosocial del paciente (6).

MECANISMOS ETIOPATOGÉNICOS

Bases histopatológicas

En articulaciones artrósicas podemos encontrar afectación del cartílago articular, consistente en adelgazamiento, fisuración con aparición de grietas verticales y fragmentación de la superficie cartilaginosa (7). Se produce además un aumento del remodelado óseo, así como la invasión de yemas vasculares responsables de perpetuar un proceso inflamatorio crónico que provocaría una hiperplasia sinovial (8), favorecería el crecimiento óseo no solo subcondral, sino que también en los márgenes articulares con la aparición de osteofitos (8) y estimularía el crecimiento de nervios sensitivos (7,9,10). Algunos autores apuntan a que este constante proceso de formación y destrucción secundario a la inflamación podría explicar al menos parcialmente el dolor, en especial si se asocia a un componente neuropático (11,12).

Además de la afectación del cartílago y la membrana sinovial, otras estructuras articulares se ven afectadas, como es el hueso subcondral, que sufrirá un fenómeno de esclerosis, los ligamentos y la musculatura articular. La inflamación sinovial da lugar a un aumento de la cantidad de líquido sinovial, provocando la hinchazón articular con distensión de la cápsula. Se ha determinado que esta distensión capsular, provoca una inhibición yatrogénica a través de un reflejo espinal de la musculatura articular, ya debilitada consecuencia de la falta de uso, dando lugar a la atrofia muscular (13).

El cartílago normal está formado por solo un 5 % de condrocitos (14), que se encargan de mantener el equilibrio entre la producción y degradación enzimática de la matriz extracelular. Su alteración a favor de un catabolismo daría lugar a un descenso en la celularidad por apoptosis con una consecuente pérdida del cartílago. Se sospecha que esta apoptosis juega un importante papel en la génesis del proceso (15,16).

Está descrito un proceso de reparación lento y efectivo que podría explicar parcialmente la ausencia de síntomas en algunos pacientes (17).

Factores de riesgo

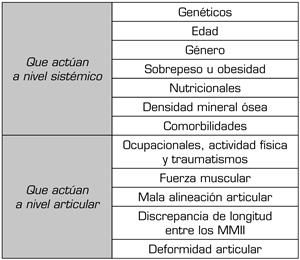

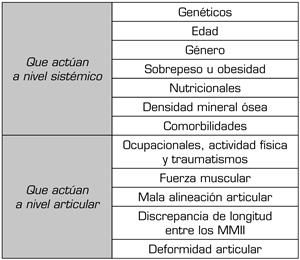

La artrosis tiene una etiología multifactorial y muy compleja. Existen una serie de factores biomecánicos, bioquímicos y genéticos que actuaría de manera coincidente hasta el deterioro articular (18,19). Los factores de riesgo son muy variables entre individuos, articulaciones y estadio de la enfermedad (20)y generalmente se dividen en dos grupos: aquellos que actúan a nivel sistémicos y los que actúan a nivel articular (Tabla I).

Tabla I. Factores de riesgo de artrosis

Factores de riesgo que actúan a nivel sistémico

- Factores genéticos. Podría existir un condicionamiento genético que explicaría una mayor frecuencia de artrosis en gemelos, aunque estos son mayoritariamente desconocidos (21), con algunas excepciones, como ocurre con el factor genético FRZB (Frizzled Related Protein), que se asocia a un mayor riesgo de artrosis de la cadera en mujeres (22). La transmisión habitualmente sigue las leyes de Mendel, por lo que es posible encontrar casos familiares.

La expresión de los genes relacionados con el cartílago (SOX9, ACAN, COL2A1, DKK1, FRZB) disminuyen durante la progresión de la enfermedad, mientras que aquellos relacionados con la hipertrofia o con la artrosis (RUNX2, COL10A1, COL1A1, IHH, AXIN2) aumentan. Estas diferencias en la expresión génica nos proporcionan un perfil de expresión génica específico de cada etapa de la artrosis, que se podría utilizar para estratificar la enfermedad a nivel molecular y en última instancia, para una orientación terapéutica (23).

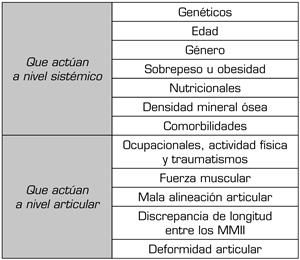

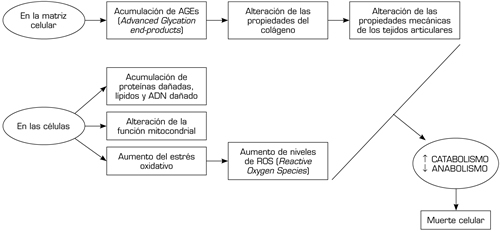

- Edad. Es un importante factor de riesgo para el desarrollo de la artrosis, al hacer a las articulaciones más vulnerables, consecuencia de una menor capacidad de reparación y mantenimiento de los condrocitos, menor capacidad de mitosis y síntesis, dando lugar a proteoglicanos de menor calidad (24). Esta peor capacidad de respuesta es especialmente crítica ante otros procesos asociados a la edad, como son los cambios hormonales y determinadas exposiciones medioambientales (25). Se han determinado una serie de cambios relacionados con la edad que favorecen la aparición y el desarrollo de la artrosis (Figura 1) (26).

Fig. 1. Cambios relacionados con la edad en la matriz extrarticular y las células.

- Género. Las mujeres presentan mayor riesgo de artrosis que los hombres, aunque estas diferencias son menores según aumenta la edad (27). Estos datos se han confirmado en la artrosis de las manos, donde el riesgo es 4 veces mayor para las mujeres de edad comprendida entre los 50 y 55 años (28). Una posible explicación no confirmada serían la presencia de receptores estrogénicos en los condrocitos cuya acción regularía positivamente la síntesis de proteoglicanos, disminuyendo a partir de la menopausia (29).

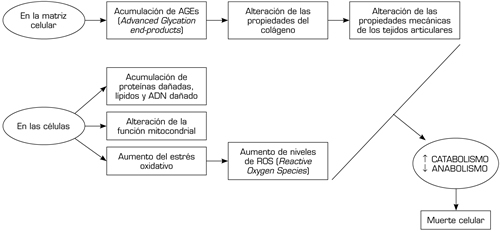

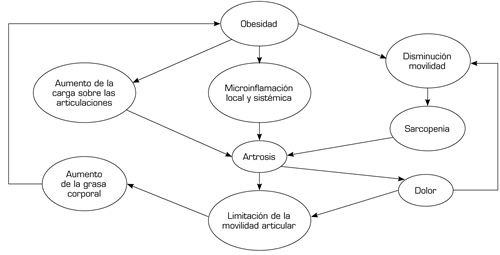

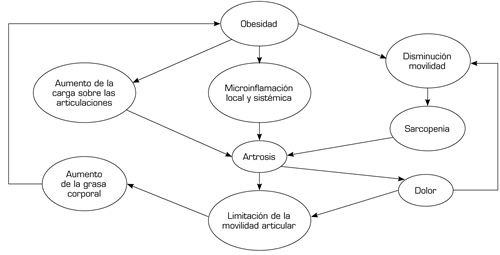

- Sobrepeso y obesidad. Existe una clara relación con la artrosis, especialmente cuando afecta a las rodillas y caderas, consecuencia del exceso de carga que tienen que soportar, aunque también ocurre en las manos, por lo que se plantea que otros factores influyen de manera considerable en su génesis (30).

La grasa corporal tiene un efecto proinflamatorio (31,32), dando lugar a una inflamación de bajo grado que actualmente se relaciona con la artrosis, actuando de manera local y también sistémica (31) (Figura 2). Existen datos en nuestros días del papel de los adipocitos en la regulación celular de diferentes tejidos como el hueso y cartílago, y podría estar implicado en la fisiopatología de la artrosis (33).

Fig. 2. Interrelación de los factores asociados a la obesidad.

- Factores nutricionales. Los condrocitos producen diferentes tipos de oxígeno reactivo que puede dañar el colágeno y el hialuronato del cartílago y líquido articular respectivamente (34). El consumo de dietas ricas en agentes antioxidantes podría tener un efecto protector en la artrosis, aunque de momentos los resultados son contradictorios.

Algunos datos apuntan a que mantener bajos niveles de vitamina D se relaciona con la presencia de artrosis de la cadera (35). Un reciente estudio del efecto de la vitamina D en la artrosis de la rodilla mediante las imágenes de la RMN, no encontró diferencias con el grupo placebo (36), aunque por cuestiones éticas, el grupo placebo recibió 400 UI/día de vitamina D, que pudo influir en los resultados. Las vitaminas C y E que poseen un efecto antioxidante y la vitamina K podrían asociarse a un efecto reductor de la progresión de la artrosis de rodilla (37), aunque los resultados son contradictorios (38,39,40).

Unos niveles bajos de selenio medidos en las uñas se asocian a una mayor incidencia de artrosis en la rodilla radiológica, sintomática y bilateral (41).

- Densidad mineral ósea (DMO). Algunos estudios apuntan a que una elevada DMO se asociaría con un aumento de la artrosis y a una disminución del espacio articular, pero no a una mayor progresión de la enfermedad (42), que podría estar en relación con el aumento del IMC resultante de esta situación. Aunque la DMO elevada podría favorecer la artrosis, en general los pacientes artrósicos tienen una menor DMO consecuencia del descenso de la actividad física que produce (43).

- Comorbilidades. La mayoría de los pacientes con artrosis tienen comorbilidades generalmente asociadas a la edad (44). La diabetes mellitus tipo 2 incide significativamente en el riesgo de desarrollar artrosis, a través del incremento de los factores proinflamatorios (TNFa, IL-6, etc.) (45).

Factores de riesgo que actúan a nivel articular

- Factores ocupacionales, actividad física y traumatismos. Cualquier actividad laboral que requiera la utilización repetitiva de una articulación supone un incremento del riesgo para desarrollar artrosis, tener una peor morfología del cartílago articular, especialmente si hablamos de articulaciones de los miembros inferiores (MMII) en pacientes con sobrepeso u obesidad o que desempeñan trabajos que requieran levantar pesos. En ellos es más frecuente tener imágenes alteradas de la articulación patelofemoral en una RM (46).

Un reciente metanálisis establece un riesgo 1,6 veces superior de desarrollar artrosis de rodilla al realizar determinadas actividades laborales que requieran sobreesfuerzos como trabajadores manuales, deportistas de élite, trabajos que requieran estar de rodillas o en cuclillas y levantar o llevar pesos, frente a aquellos que precisan permanecer en bipedestación o que sean trabajos sedentarios (47). Aquellas actividades que precisan levantarse de forma continuada o mantener una bipedestación prolongada, aumentan el riesgo de desarrollar una artrosis de cadera (48,49).

Por otro lado, aquellos trabajos que requieran realizar actividades manuales de repetición, como hacer la pinza, aumentan el riesgo de artrosis de las manos (50).

Si bien la actividad física puede producir beneficios en las articulaciones al aumentar la masa muscular, y por tanto fortalecerla sin aumentar el riesgo de artrosis, también puede ser potencialmente perjudicial si existiera una zona dañada previamente (51,52).

La actividad deportiva de élite puede asociarse a un aumento del riesgo de artrosis, aunque es necesario que coexistan otros factores de riesgo, como ocurre en la artrosis de rodilla en deportistas con traumatismos repetitivos, con elevado IMC o las sentadillas entre los levantadores de pesos (53).

Los traumatismos en la rodilla que provoquen una rotura meniscal o del ligamento cruzado anterior y requiera reparación quirúrgica son factores de riesgo para desarrollar artrosis (54,55,56). Existen dos metanálisis que sugieren que los traumatismos articulares incrementan cuatro veces el riesgo de artrosis (57,58). Además, hay que tener en cuenta que una intervención quirúrgica para la reparación de una rotura meniscal o ligamentaria no hace disminuir el riesgo de desarrollar artrosis de la rodilla (59).

Es interesante destacar la relación controvertida entre la artrosis y las fracturas. Algunos estudios apuntan a que la presencia de artrosis se asocia a una disminución de las fracturas (60), mientras que otros no encuentran ese efecto protector (61). Probablemente la esclerosis subcondral y la presencia de osteofitos tenga la capacidad de reducir las fracturas pero limitado a esas zonas, mientras que como es característico de la artrosis el resto del hueso se asocia a una menor DMO y mayor predisposición a fracturarse.

Las fracturas especialmente si son intrarticulares predisponen a la artrosis, como ocurre con las fracturas de la meseta tibial que se asocian a dolor, limitación de la movilidad articular, deformidad angular, inestabilidad y artrosis de rodilla, con una frecuencia entre un 26 a un 52 % en 2 años (62,63).

- Fuerza muscular. Las lesiones en la rodilla se relacionan con la aparición de artrosis, consecuencia de la falta de movilidad y atrofia del cuádriceps (64,65), sin embargo, un cuádriceps potente en rodillas con laxitud ligamentaria o con mala alineación articular puede determinar un adelgazamiento del cartílago patelofemoral (66).

- Mala alineación articular. La deformidad en varo de la rodilla se asocia al desarrollo de artrosis y deterioro del cartílago del compartimiento medial (67,68). Se produce un círculo vicioso, en el cual la deformidad articular produce una disminución del espacio articular medial que provocará el aumento de la deformidad, alterando la distribución de las cargas y favoreciendo la progresión de la artrosis (69).

- Discrepancia de longitud entre los MMII. Diferentes estudios han demostrado la relación existente entre una diferencia de longitud superior a 1 o 2 cm en una pierna y el desarrollo de artrosis en la rodilla de la pierna más corta (70,71,72).

- Deformidad articular. La deformidad de la articulación altera el reparto de la carga sobre los diferentes tejidos articulares y se asocia al desarrollo de artrosis (73,74). La displasia acetabular y el síndrome del choque femoroacetabular de la cadera, ya sea tipo CAM o PINCER, se asocian a artrosis de cadera (75,76).

CONCLUSIONES

La artrosis es una enfermedad incurable cuyo origen es multifactorial. Existen bases histológicas que ayudan a explicar las discrepancias clínicas existentes entre los pacientes. Su aparición está condicionada por diferentes factores de riesgo, algunos de ellos modificables. Estos factores de riesgo actuarían de manera coincidente alterando las propiedades de los tejidos articulares y la biomecánica articular, dando lugar al deterioro de la articulación. A pesar de todo, no está claro los mecanismos directos por los cuales actuarían la mayoría de estos factores de riesgo. El esclarecimiento de estos mecanismos podría establecer diferentes objetivos para un óptimo tratamiento en un futuro.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

- Hamerman D. Aging and osteoarthritis: basic mechanisms. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(7):760-70. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07469.x.

- Eumusc.net. Musculoskeletal Health in Europe 2011 [Internet]. 2011 [consultado el 18 de octubre de 2020]. Disponible en: http://www.eumusc.net/myUploadData/files/Musculoskeletal%20Health%20in%20Europe%20Report%20v5.pdf

- van der Kraan PM. Osteoarthritis year 2012 in review: biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(12):1447-50. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.07.010.

- Hunter DJ. Focusing osteoarthritis management on modifiable risk factors and future therapeutic prospects. Ther Adv Musculoskel Dis. 2009;1(1):35-47. DOI: 10.1177/1759720X09342132.

- Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Anthony JM, Zhang Y, Wilson PW, et al. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(3):351-8. DOI: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.351.

- Arden N, Nevitt MC. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20(1):3-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.09.007.

- Madry H, Luyten FP, Facchini A. Biological aspects of early osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(3):407-22. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-011-1705-8.

- Hernandez-Molina G, Neogi T, Hunter DJ, Niu J, Guermazi A, Reichenbach S, et al. The association of bone attrition with knee pain and other MRI features of osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(1):43-7. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2007.070565.

- Suri S, Gill SE, Massena de Camin S, Wilson D, McWilliams DF, Walsh DA. Neurovascular invasion at the osteochondral junction and in osteophytes in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(11):1423-8. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2006.063354.

- Mapp P, Walsh DA Mechanisms and targets of angiogenesis and nerve growth in osteoarthritis Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(7):390-8. DOI: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.80.

- Ivanavicius SP, Ball AD, Heapy CG, Westwood FR, Murray F, Read SJ. Structural pathology in a rodent model of osteoarthritis is associated with neuropathic pain: increased expression of ATF-3 and pharmacological characterisation. Pain. 2007;128(3):272-82. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.022.

- Oteo-Álvaro A, Ruiz-Ibán MA, Miguens X, Stern A, Villoria J, Sánchez-Magro I. High prevalence of neuropathic pain features in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Pain Pract. 2015;15(7):618-26. DOI: 10.1111/papr.12220.

- Neogi T, Felson D, Niu J, Lynch J, Nevitt M, Guermazi A, et al. Cartilage loss occurs in the same subregions as subchondral bone attrition: a within-knee subregion-matched approach from the Multicenter. Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(11):1539-44. DOI: 10.1002/art.24824.

- Kuettner KE. Biochemistry of articular cartilage in health and disease. Clin Biochem 1992;25(3):155-63. DOI: 10.1016/0009-9120(92)90224-g.

- Aigner T, Hemmel M, Neureiter D, Gebhard PM, Zeiler G, Kirchner T, et al. Apoptotic cell death is not a widespread phenomenon in normal aging and osteoarthritic human articular knee cartilage: a study of proliferation, programmed cell death (apoptosis), and viability of chondrocytes in normal and osteoarthritic human knee cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(6):1304-12. DOI: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1304::AID-ART222>3.0.CO;2-T.

- Kouri JB, Jimenez SA, Quintero M, Chico A. Ultrastructural study of chondrocytes from fibrillated and non-fibrillated human osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1996;4(2):111-25. DOI: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80320-6.

- Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(1):16-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012.

- Goldring MB. The role of the chondrocyte in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(9):1916-26. DOI: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1916::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-I.

- Westacott CI, Sharif M. Cytokines in osteoarthritis: mediators or markers of joint destruction? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996;25(4):254-72. DOI: 10.1016/s0049-0172(96)80036-9.

- Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden NK, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(4):476-99. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013.

- van Meurs JB, Uitterlinden AG. Osteoarthritis year 2012 in review: genetics and genomics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(12):1470-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.08.007.

- Loughlin J. The genetic epidemiology of human primary osteoarthritis: current status. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7(9):1-12. DOI: 10.1017/S1462399405009257.

- Zhong L, Huang X, Karperien M, Post JN. Correlation between gene expression and osteoarthritis progression in human. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(7):1126. DOI: 10.3390/ijms17071126.

- Abramson SB, Attur M. Developments in the scientific understanding of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):227. DOI: 10.1186/ar2655.

- Petersson IF, Jacobsson LT. Osteoarthritis of the peripheral joints. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16(5):741-60. DOI: 10.1053/berh.2002.0266.

- Loeser RF, Collins JA, Diekman BO. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(7):412-20. DOI: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.65.

- Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(8):1343-55. DOI: 10.1002/1529-0131(199808)41:8<1343::AID-ART3>3.0.CO;2-9.

- Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, Javaid MK, Cooper C, Diez-Perez A, Arden NK. Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(9):1659-64. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203355.

- Hanna FS, Wluka AE, Bell RJ, Davis SR, Cicuttini FM. Osteoarthritis and the postmenopausal woman: Epidemiological, magnetic resonance imaging, and radiological findings. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34(3):631-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.07.007.

- Reyes C, Leyland KM, Peat G, Cooper C, Arden NK, Prieto-Alhambra D. Association Between Overweight and Obesity and Risk of Clinically Diagnosed Knee, Hip, and Hand Osteoarthritis: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(8):1869-75. DOI: 10.1002/art.39707.

- van der Kraan PM. Osteoarthritis year 2012 in review: biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(12):1447-50. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.07.010.

- Madry H, Luyten FP, Facchini A. Biological aspects of early osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(3):407-22. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-011-1705-8.

- Teichtahl AJ, Wang Y, Wluka AE, Cicuttini FM. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis: new insights provided by body composition studies. Obesity. 2008;16(2):232-40. DOI: 10.1038/oby.2007.30.

- Ameye LG, Chee WS. Osteoarthritis and nutrition. From nutraceuticals to functional foods: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R127. DOI: 10.1186/ar2016.

- Lane NE, Oehlert JW, Bloch DA, Fries JF. The relationship of running to osteoarthritis of the knee and hip and bone mineral density of the lumbar spine: a 9-year longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(2):334-41.

- McAlindon TE, Dawson-Huges B, Driban J, Nuite M, Lee JY, Priceet LL, et al. Clinical trial of vitamin D to reduce pain and structural progression of knee osteoarthritis (OA). Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:S294

- McAlindon T, Felson DT. Nutrition: risk factors for osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(7):397-400. DOI: 10.1136/ard.56.7.397.

- Peregoy J, Wilder FV. The effects of vitamin C supplementation on incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14(4):709-15. DOI: 10.1017/S1368980010001783.

- Wluka AE, Stuckey S, Brand C, Cicuttini FM. Supplementary vitamin E does not affect the loss of cartilage volume in knee osteoarthritis: a 2 year double blind randomized placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2585-91.

- Neogi T, Felson DT, Sarno R, Booth SL. Vitamin K in hand osteoarthritis: results from a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1570-3. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2008.094771.

- Jordan JM, Fang F, Arab L. Low selenium levels are associated with increased risk for osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:S455.

- Nevitt MC, Zhang Y, Javaid MK, Neogi T, Curtis JR, Niu J, et al. High systemic bone mineral density increases the risk of incident knee OA and joint space narrowing, but not radiographic progression of existing knee OA: the MOST study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):163-8. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2008.099531.

- Li B, Aspden RM. Composition and mechanical properties of cancellous bone from the femoral head of patients with osteoporosis or osteoarthritis. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(4):641-51. DOI: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.641.

- Kadam UT, Jordan K, Croft PR. Clinical comorbidity in patients with osteoarthritis: a case-control study of general practice consulters in England and Wales. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(4):408-14. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2003.007526.

- Duclos M. Osteoarthritis, obesity and type 2 diabetes: The weight of waist circumference. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(3):157-60. DOI: 10.1016/j.rehab.2016.04.002.

- Amin S, Goggins J, Niu J, Guermazi A, Grigoryan M, Hunter DJ, et al. Occupation-related squatting, kneeling, and heavy lifting and the knee joint: a magnetic resonance imaging-based study in men. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(8):1645-9.

- McWilliams DF, Leeb BF, Muthuri SG, Doherty M, Zhang W. Occupational risk factors for osteoarthritis of the knee: a meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):829-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.016.

- Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, Coggon D. Osteoarthritis of the hip and occupational activity. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992;18(1):59-63. DOI: 10.5271/sjweh.1608.

- Yoshimura N, Sasaki S, Iwasaki K, Danjoh S, Kinoshita H, Yasuda T, et al. Occupational lifting is associated with hip osteoarthritis: a Japanese case-control study. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(2):434-40.

- Hadler NM, Gillings DB, Imbus HR, Levitin PM, Makuc D, Utsinger PD, et al. Hand structure and function in an industrial setting. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21(2):210-20. DOI: 10.1002/art.1780210206.

- McAlindon TE, Wilson PW, Aliabadi P, Weissman B, Felson DT. Level of physical activity and the risk of radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham study. Am J Med. 1999;106(2):151-7. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00413-6.

- Wang Y, Simpson JA, Wluka AE, Teichtahl AJ, English DR, Giles GG, et al. Is physical activity a risk factor for primary knee or hip replacement due to osteoarthritis? A prospective cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(2):350-7. DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.091138.

- Kujala UM, Kettunen J, Paananen H, Aalto T, Battié MC, Impivaara O, et al. Knee osteoarthritis in former runners, soccer players, weight lifters, and shooters. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(4):539-46. DOI: 10.1002/art.1780380413.

- Lohmander LS, Ostenberg A, Englund M, Roos H. High prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitations in female soccer players twelve years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3145-52. DOI: 10.1002/art.20589.

- Roos EM, Ostenberg A, Roos H, Ekdahl C, Lohmander LS. Long-term outcome of meniscectomy: symptoms, function, and performance tests in patients with or without radiographic osteoarthritis compared to matched controls. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(4):316-24. DOI: 10.1053/joca.2000.0391.

- Englund M, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Aliabadi P, Yang M, Lewis CE, et al. Meniscal tear in knees without surgery and the development of radiographic osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly persons: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(3):831-9. DOI: 10.1002/art.24383.

- Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan KP. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(1):24-33. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.010.

- Muthuri SG, McWilliams DF, Doherty M, Zhang W. History of knee injuries and knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(11):1286-93. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.07.015.

- Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1756-69. DOI: 10.1177/0363546507307396.

- Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Osteoarthritis and risk of fractures. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;84(4):249-56. DOI: 10.1007/s00223-009-9224-z.

- Davies JH, Centomo H, Leduc S, Beaumont P, Laflamme GY, Rouleau DM. Preexisting carpal and carpometacarpal osteoarthritis has no impact on function after distal radius fractures. J Wrist Surg. 2017;6(4):301-6. DOI: 10.1055/s-0037-1602800.

- Dustmann HO, Schulitz KP. Conservative and operative treatment of fractures of the head of tibia. Z Orthop Grenzgeb. 1973;111(2):160-8.

- Manidakis N, Dosani A, Dimitriou R, Stengel D, Matthews S, Giannoudis P. Tibial plateau fractures: functional outcome and incidence of osteoarthritis in 125 cases. Int Orthop. 2010;34(4):565-70. DOI: 10.1007/s00264-009-0790-5.

- Brandt KD, Heilman DK, Slemenda C, Katz BP, Mazzuca SA, Braunstein EM, et al. Quadriceps strength in women with radiographically progressive osteoarthritis of the knee and those with stable radiographic changes. J Rheumatol.1999;26(11):2431-7.

- Slemenda C, Heilman DK, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Mazzuca SA, Braunstein EM, et al. Reduced quadriceps strength relative to body weight: a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(11):1951-9. DOI: 10.1002/1529-0131(199811)41:11<1951::AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-9.

- Amin S, Baker K, Niu J, Clancy M, Goggins J, Guermazi A, et al. Quadriceps strength and the risk of cartilage loss and symptom progression in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(1):189-98. DOI: 10.1002/art.24182.

- Sharma L, Chmiel JS, Almagor O, Felson D, Guermazi A, Roemer F, et al. The role of varus and valgus alignment in the initial development of knee cartilage damage by MRI: the MOST study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):235-40. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201070.

- Sharma L, Song J, Dunlop D, Felson D, Lewis CE, Segal N, et al. Varus and valgus alignment and incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):1940-5. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2010.129742.

- Segal NA, Anderson DD, Iyer KS, Baker J, Torner JC, Lynch JA, et al. Baseline articular contact stress levels predict incident symptomatic knee osteoarthritis development in the MOST cohort. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(12):1562-8. DOI: 10.1002/jor.20936.

- Golightly YM, Allen KD, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Hazard of Incident and Progressive Knee and Hip Radiographic Osteoarthritis and Chronic Joint Symptoms in Individuals with and without Limb Length Inequality. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(10):2133-40. DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.091410.

- Golightly YM, Allen KD, Renner JB, Helmick CG, Salazar A, Jordan JM. Relationship of limb length inequality with radiographic knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(7):824-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.009.

- Harvey WF, Yang M, Cooke TD, Segal NA, Lane N, Lewis CE, et al. Association of leg-length inequality with knee osteoarthritis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(5):287-95. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00006.

- Lynch JA, Parimi N, Chaganti RK, Nevitt MC, Lane NE. The association of proximal femoral shape and incident radiographic hip OA in elderly women. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(10):1313-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.011.

- Lane NE, Lin P, Christiansen L, Williams EN, Hochberg MC, Nevitt MC. Association of mild acetabular dysplasia with an increased risk of incident hip osteoarthritis in elderly white women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(2):400-4. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<400::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-D.

- Doherty M, Courtney P, Doherty S, Jenkins W, Maciewicz RA, Muir K, et al. Nonspherical femoral head shape (pistol grip deformity), neck shaft angle, and risk of hip osteoarthritis: a case-control study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):3172-82. DOI: 10.1002/art.23939.

- Reid GD, Reid CG, Widmer N, Munk PL. Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: an underrecognized cause of hip pain and premature osteoarthritis? J Rheumatol. 2010;37(7):1395-404. DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.091186.