10.20986/resed.2025.4157/2024

REVISIÓN

Integrating pain science education in a multicomponent treatment for individuals with fibromyalgia: a practical guide for clinicians

Integrando la educación en ciencia del dolor en un tratamiento multicomponente para personas con fibromialgia: una guía práctica clínica

Mayte Serrat López1

Estíbaliz Royuela-Colomer2

Jo Nijs3,4,5

Xavier Borràs Hernández6,7

Juan V. Luciano Devis2,7,8

Rubén Nieto Luna9

Albert Feliu-Soler2,7

1Unitat d’Expertesa en Síndromes de Sensibilització Central. Servei de Reumatologia. Vall d’Hebron Hospital Universitari. Barcelona, Spain

2Department of Clinical and Health Psychology. Autonomous University of Barcelona. Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Barcelona, Spain

3Pain in Motion Research Group (PAIN). Department of Physical Therapy, Human Physiology and Anatomy. Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

4Chronic pain rehabilitation. Department of Physical Medicine and Physical Therapy. University Hospital Brussels, Belgium

5Department of Health and Rehabilitation. Unit of Physical Therapy. Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology. Sahlgrenska Academy. University of Gothenburg, Sweden

6Department of Basic, Developmental and Educational Psychology. Autonomous University of Barcelona. Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Barcelona, Spain

7Centre for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP). Madrid, Spain

8Teaching, Research & Innovation Unit, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, St. Boi de Llobregat, Spain

9Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain

ABSTRACT

There is a growing body of literature acknowledging the significance of integrating multiple therapeutic components to effectively manage the wide range of symptoms related to fibromyalgia (FM). Empirically supported approaches such as pain science education, therapeutic physical exercise programs, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) have garnered considerable attention. The FIBROWALK program incorporates Pain Science Education (PSE) as its core component. This comprehensive program amalgamates diverse components, including therapeutic physical exercise designed to engage cognitive and emotional targets through dual tasks, and adhering to the transtheoretical model of stages of change. Additionally, it integrates CBT and mindfulness training to enhance self-management strategies by reshaping biased pain cognitions and negative beliefs. The program aims to instigate behavioural change by employing motivational interviewing (MI) as the primary communication style. Its ultimate objective lies in fostering lifestyle changes that ensure the sustainability of benefits, thereby enhancing outcomes with more significant and enduring effects. Multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have assessed the effectiveness of FIBROWALK, consistently revealing moderate-to-large effect sizes across core FM-related outcomes. This article provides a practical guide for clinicians, offering insights into seamlessly integrating PSE within a multicomponent treatment package for individuals with FM.

Key words: Fibromyalgia, pain science education, exercise therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness, motivational interviewing, multicomponent treatment

RESUMEN

Existe una creciente literatura que reconoce la importancia de integrar múltiples componentes terapéuticos para controlar eficazmente la amplia gama de síntomas relacionados con la fibromialgia (FM). Los enfoques respaldados empíricamente, como la educación en ciencia del dolor (PSE), los programas de ejercicio físico terapéutico y la terapia cognitivo-conductual (TCC), han atraído considerable atención. El programa FIBROWALK incorpora PSE como su componente principal. No obstante, este programa integral amalgama diversos componentes, incluido el ejercicio físico terapéutico diseñado para involucrar objetivos cognitivos y emocionales a través de tareas duales y adhiriéndose al modelo transteórico de etapas de cambio. Además, integra la TCC y el entrenamiento de atención plena para mejorar las estrategias de autocontrol al reestructurar las cogniciones sesgadas sobre el dolor y las creencias negativas. El programa FIBROWALK tiene como objetivo provomer un cambio de comportamiento mediante el empleo de la entrevista motivacional (EM) como estilo de comunicación principal. Su objetivo final radica en fomentar cambios en los estilos de vida que aseguren la sostenibilidad de los beneficios, mejorando así los resultados con efectos más significativos y duraderos. Múltiples ensayos clínicos aleatorizados (ECA) han evaluado la efectividad de FIBROWALK, revelando consistentemente tamaños de efecto de moderados a grandes en los principales resultados relacionados con la FM. Este artículo proporciona una guía práctica para los profesionales sanitarios y ofrece información sobre cómo integrar la PSE dentro de un paquete de tratamiento multicomponente para personas con FM.

Palabras clave: Fibromialgia, educación en ciencia del dolor, ejercicio terapéutico, terapia cognitivo-conductual, atención plena, entrevista motivacional, tratamiento multicomponente.

Correspondencia

Mayte Serrat López

mayte.serrat@vallhebron.cat

Recibido: 18-05-2024

Aceptado: 31-01-2025

BACKGROUND

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic syndrome characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, stiffness, and other concomitant cognitive and emotional symptoms (1). Despite these manifestations, no identifiable structural pathology in muscles, tendons, ligaments, or joints is known to cause FM. This condition stands as one of the most prevalent worldwide (2), predominantly affecting women3. Globally, it holds an estimated prevalence of 2 % within the general population (3), while in Spain, the prevalence is estimated at 2.45 % (4).

The socioeconomic impact of FM is substantial, imposing significant costs on healthcare systems and society at large (5). It holds the unfortunate distinction of being the chronic pain condition with the highest rates of unemployment, sick leave, disability claims, work absenteeism, and elevated per-patient costs (5,6).

Although the etiopathophysiology of FM remains elusive, emerging evidence suggests the involvement of an imbalance within the central nervous system (CNS) between inhibitory and facilitatory pain pathways (7,8). This imbalance is thought to play a pivotal role in both the onset and chronification of pain associated with FM (9,10). Indeed, the experience of pain in FM is a complex interplay of factors, primarily attributed to functional changes within the CNS. This includes amplification of sensory stimuli and continuous activation of the alarm system, triggering persistent motor, autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune-inflammatory responses in individuals affected by FM (11,12).

Although there is no definitive cure for FM, several treatment options aim to alleviate associated symptoms and enhance overall quality of life (13). Current pharmacological approaches target individual symptoms of FM, offering relatively modest clinical benefits (14). However, recent scientific understanding emphasizes a multidisciplinary treatment approach for FM, highlighting non-pharmacological treatments as pivotal in addressing its symptoms (13,15,16,17,18).

Multidisciplinary and multicomponent or multimodal approaches encompass evidence-based pharmacological treatments and non-pharmacological interventions like therapeutic physical exercise, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), or mindfulness training. Moreover, consensus among experts underscores the importance of pain education for a comprehensive treatment approach (11). This involves imparting in-depth knowledge about the biopsychosocial roots of FM. Recent research suggests incorporating pain education, aerobic exercise, and psychological interventions for effective chronic pain management (3).

Several meta-analytic studies have underscored the effectiveness of multicomponent treatments for FM, encompassing psychological or educational components coupled with physical exercise therapy (19,20). These comprehensive reviews consistently highlight both short and long-term enhancements in functionality, pain management, and coping mechanisms among persons with FM undergoing these treatments. Furthermore, research indicates broader positive outcomes post-treatment, including alleviated anxiety and depression levels, improved quality of life, and notable reductions in direct and indirect treatment costs (19,20).

THE FIBROWALK TREATMENT PROTOCOL: AN OVERVIEW

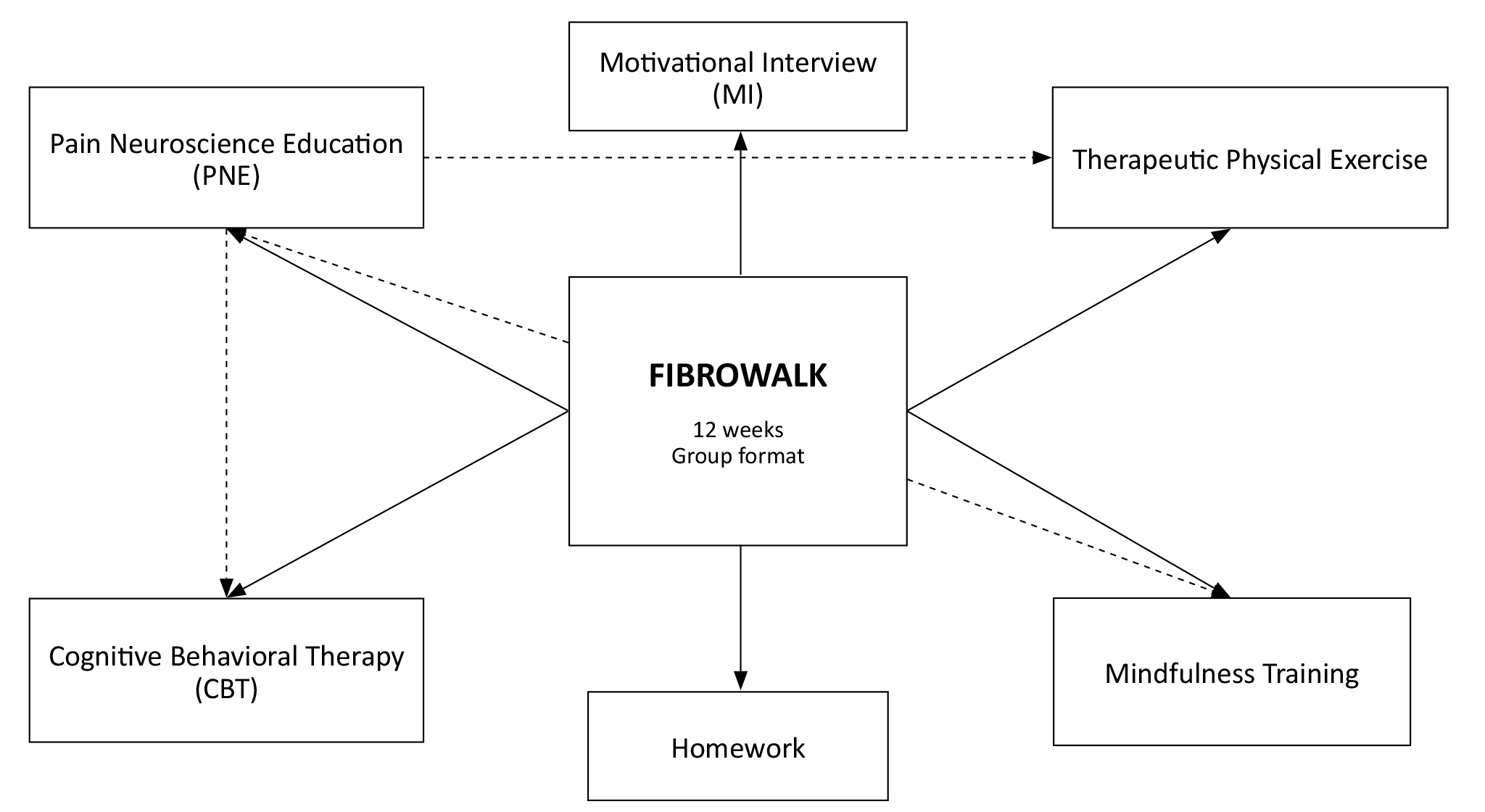

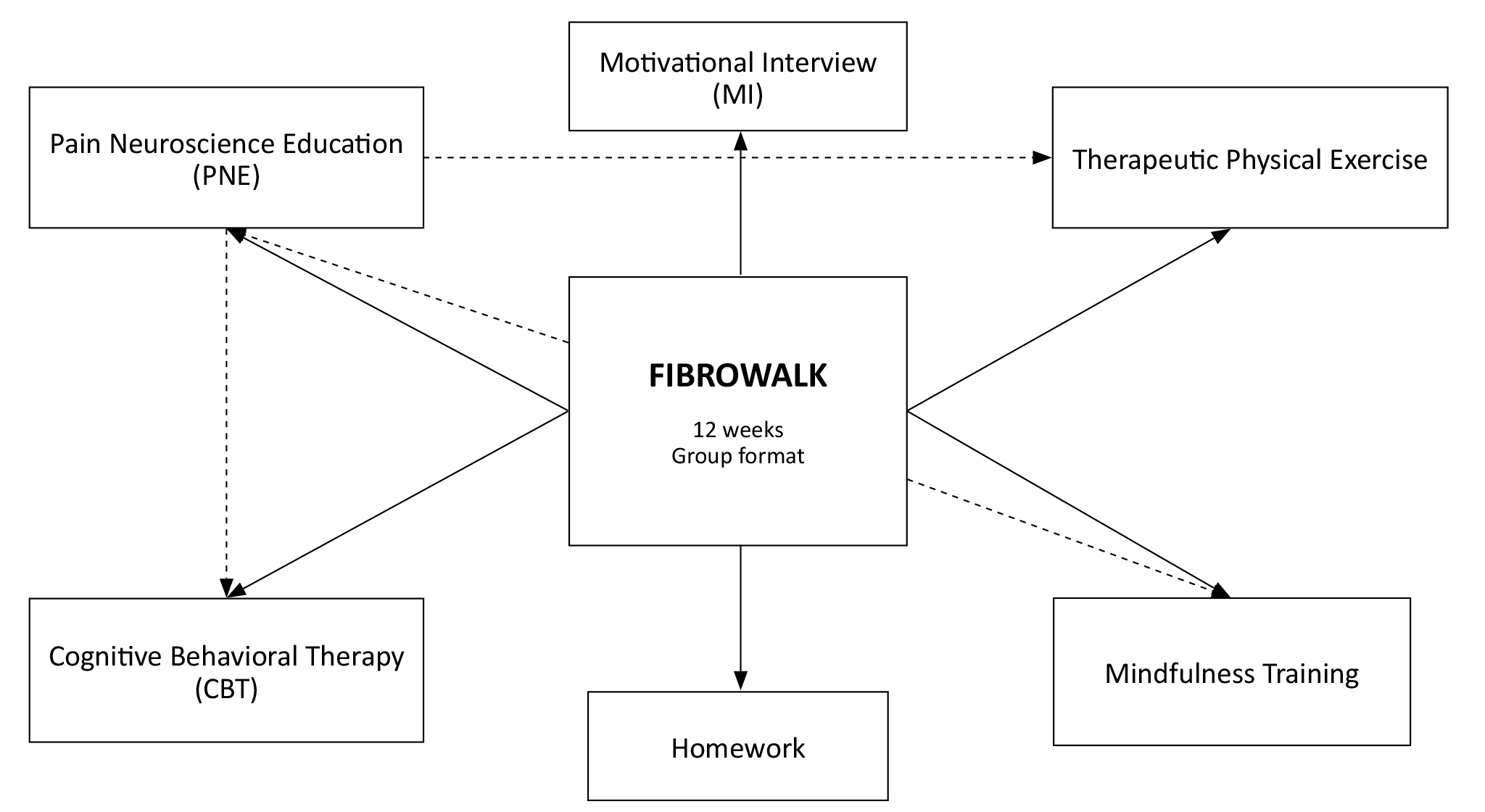

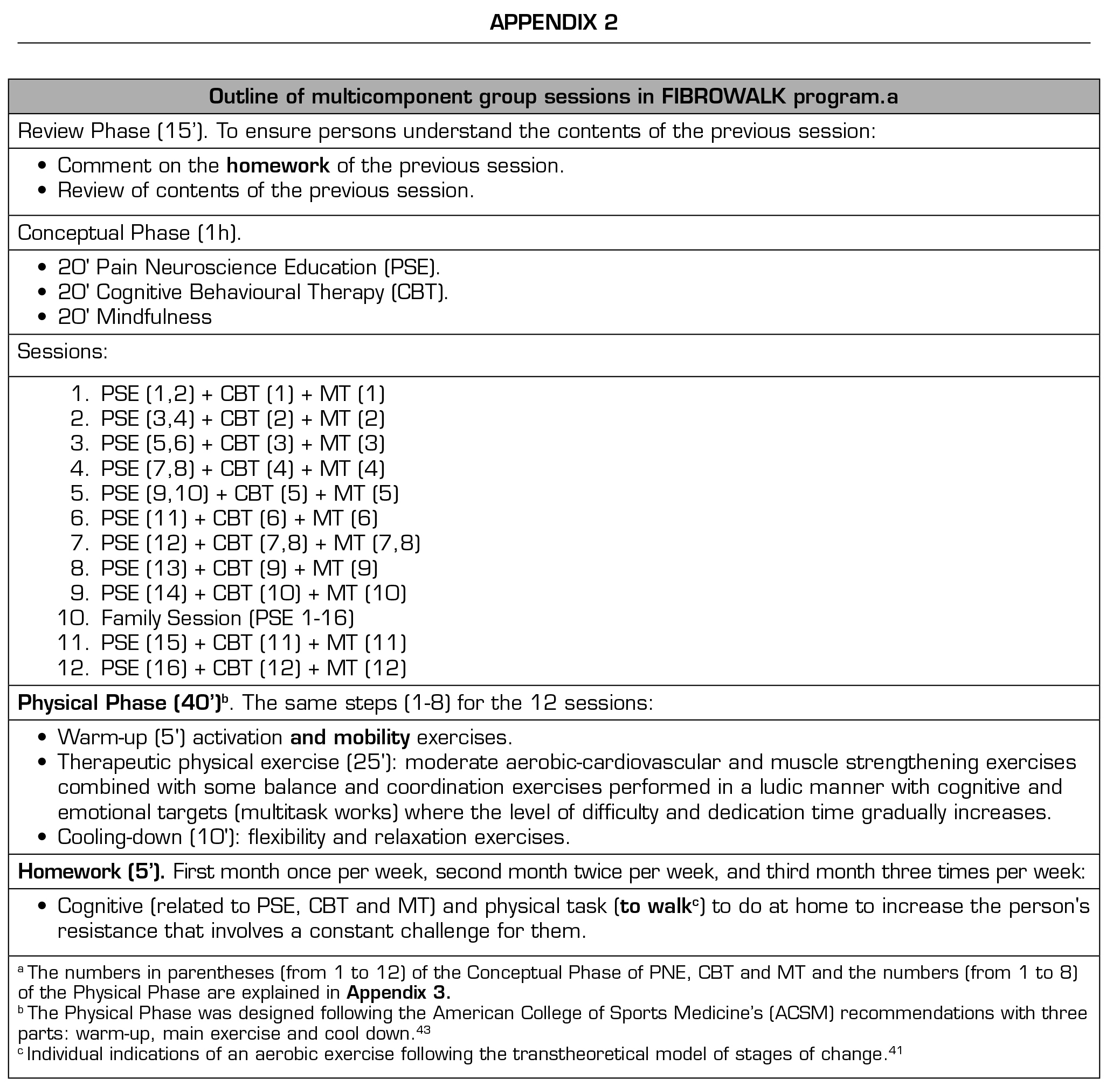

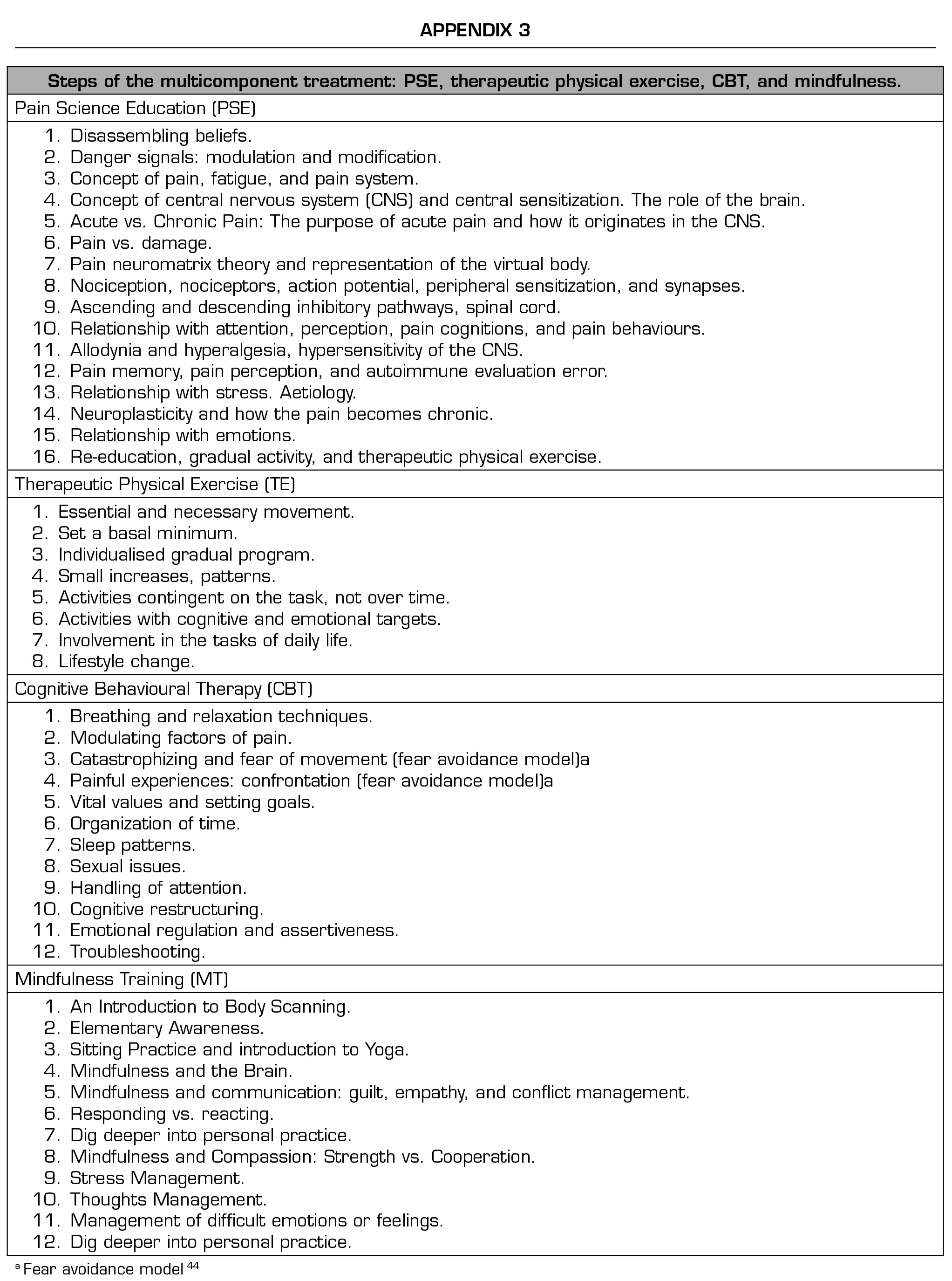

The FIBROWALK treatment was developed by Dr.Mayte Serrat, a psychologist and physiotherapist with extensive experience in the non-pharmacological management of FM. Dr. Serrat is the physiotherapist in charge of the Central Sensitivity Syndromes Unit at Vall d’Hebron Hospital in Barcelona. FIBROWALK was originally created as part of her doctoral thesis, and has been the primary treatment for FM in the unit for the past five years. This program comprises 12 weekly sessions, each lasting 2 hours and conducted in a group setting. It integrates various components: PSE, therapeutic physical exercise, CBT, and mindfulness training, illustrated in Figure 1. Individually, these elements have demonstrated efficacy in improving physical function, psychological well-being, and overall quality of life in persons with FM, aligning with contemporary evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (21,22).

PSE, an educational program that aims to change how pain is conceptualized, conveyed and explained so that individuals can re-conceptualize the meaning of the pain experience, has shown evidence of efficacy for chronic pain conditions in general and FM in particular (16,23,24). In FIBROWALK, PSE is not only a part of the multicomponent therapy, but also the fundamental component that guides the approach of all the remaining components involved. It is crucial to grasp the concepts of pain elucidated in the PSE to ensure that all strategies employed are aligned with these fundamental neuroscience principles of, avoiding potential conflicts.

The therapeutic exercise component in FIBROWALK comprises physical exercise with dual tasks that have cognitive and emotional targets, following the transtheoretical model of stages of change (4). Dual tasks involve performing two different tasks simultaneously or in close succession. The goal is to study how the brain manages or divides attention between these tasks. These tasks can range from cognitive activities (such as solving a problem while listening to instructions) to motor tasks (such as walking while talking to another person). Dual tasks serve to explore the limits and mechanisms of attention, multitasking skills, and cognitive workload. Finally, the program combines CBT (fourth generation, including knowledge of neuroscience), which has been effective in treating the main symptoms of FM (25,26), with mindfulness training, which has shown significant effects on pain intensity, anxiety, depression, and quality of life for FM (27,28).

DESCRIPTION OF FIBROWALK

Pain science education

As highlighted earlier, PSE stands as the pivotal component guiding the treatment strategies, signifying a fundamental shift in how persons with FM comprehend and process pain-related information. While PNE embodies a profound conceptual change regarding pain, a minimum application of 30-minute group sessions across 6 sessions seems imperative for its superior effectiveness over traditional psychoeducation (29). When provided in individual sessions, 2 sessions of 30 minutes each suffice (3). Despite its documented efficacy in various studies, solely applying PNE, without integrating other non-pharmacological methods, might not adequately alleviate chronic pain (30). Conversely, when combined with physical exercise, substantial enhancements across all parameters are observed, particularly when aerobic exercise is incorporated (31).

Figura 1. Components of FIBROWALK. The straight arrows represent the program components. The dashed arrows indicate relationships between elements.

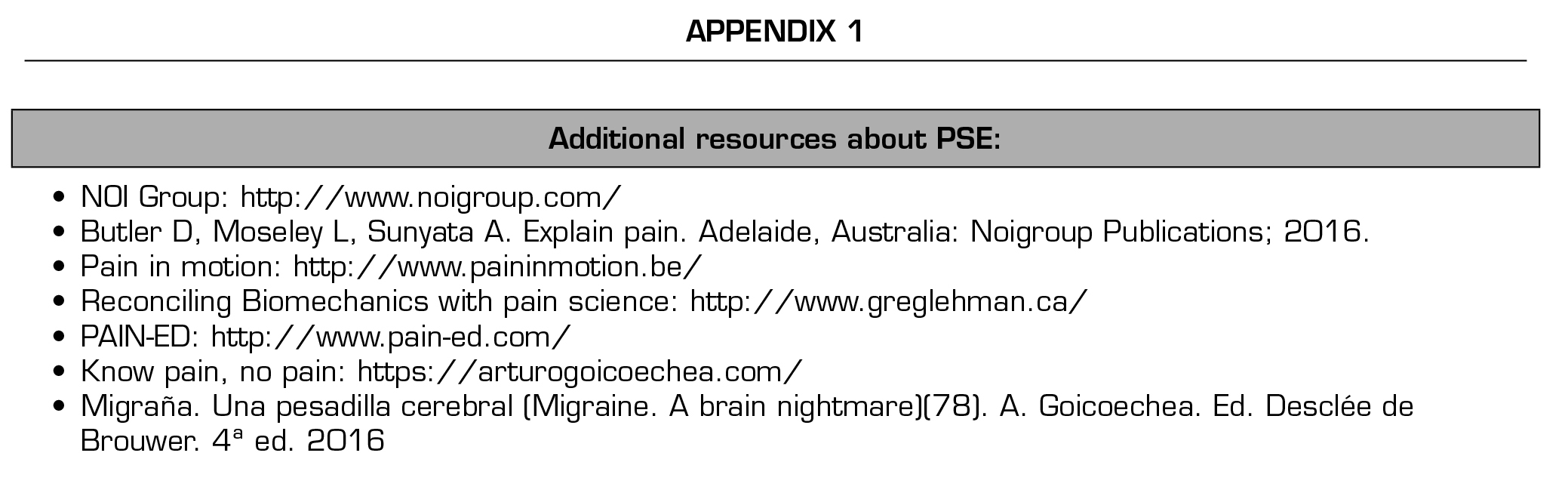

Throughout the therapy, all the contents of PNE is consistently reinforced in each session, following the book Explain Pain (32) (see Appendix 1 for additional resources). The educational content was conveyed using visual aids, real-life examples, and metaphors to enhance its comprehensibility for the participants (33). Specifically, 20 minutes of each session are dedicated to PSE, except for the final session, which lasts 2 hours and involves the families of persons with FM, summarizing the entire program (see Appendices 2 and 3). In addition, the CBT and therapeutic physical exercise components reinforce the main idea that pain is not related to damage, but to the perception of threat.

The interconnectedness between perception of threat, kinesiophobia, catastrophizing, and the fear avoidance model is significant: perceived threat can amplify the fear of movement (kinesiophobia), while catastrophizing beliefs can further heighten this sense of threat. Consequently, these reactions might prompt avoidance of activities, potentially perpetuating chronic pain. This necessitates a comprehensive assessment encompassing various physical, psychological, cognitive, and social factors. While explaining the content of PSE, one must prioritize updating individuals’ understanding, dispelling the misconception that pain correlates solely with the extent of physical damage. It is crucial to emphasize that experiencing pain without evident damage does not imply fabrication or the presence of psychological issues necessitating treatment. To facilitate this, an “expert person” (i.e., individuals highly skilled in the field) can be trained by healthcare professionals to assist in various group settings. The “expert patient” concept in FIBROWALK involves people who have personally experienced the therapy and have developed substantial knowledge and experience managing their condition. This way, these individuals can become valuable resources due to their knowledge and understanding of how to apply FIBROWALK therapy and help by providing their expertise throughout the sessions. In case the training and collaboration with such an “expert person” is not feasible, clinicians can consider collecting statements from patients who have completed the program about their experiences, and present them to the patients during the program.

Motivational interviewing (MI) strategies can be used to integrate PSE into the subsequent, and more active parts of the program, as described in detail elsewhere (34,35). MI is essential to ensure that persons fully understand the information provided to them, enabling a change in pain cognitions and maladaptive pain beliefs and thus facilitating a subsequent change in pain behaviour34. MI is an empathetic and positive person-centred communication process that aims to generate and improve an individual’s motivation to change their internal thoughts about health behaviours, decisions and personal motivation and to strengthen their commitment to change (36). It involves a collaborative and empathetic therapeutic relationship, characterized by open-ended questions, active listening, and reflection to help persons explore their ambivalence and motivations for change. Through MI, individuals are encouraged to reflect autonomously on their values and goals, and to generate their reasons and strategies for change. For an extended explanation of MI, consult Miller and Stephen (37) and Rubak and colleagues (38) (Box 1 and Supplementary Box 1). Miller and Rollnich (39) further explain what is and what is not MI.

At the beginning of each FIBROWALK session and before delving into the PSE content, approximately 15 minutes are reserved for reviewing the contents and commenting on the previous session’s homework.

During this phase, MI strategies are crucial to ensure participants grasp the prior session’s concepts, emphasizing key homework elements and revisiting previously addressed inquiries. Integrating MI across all program phases fosters a comprehensive understanding of the material, strengthens commitment to change, and facilitates the necessary behavioural adjustments for positive lifestyle change (40) and treatment adherence (41). Detailed examples of the application of MI can be found in Sobell and Sobell (25). Moreover, recent insights on its application alongside PSE have been elaborated by Nijs and colleagues (34).

Notwithstanding the above, information and motivational strategies alone may not be enough to achieve the necessary behaviour change for a correct approach to pain management. The combination of PSE and MI may be the key to paving the path for more active approaches, such as therapeutic physical exercise on a graduated exposure basis or exposure in vivo (18).

Therapeutic physical exercise

Exercise stands as the foremost non-pharmacological treatment for FM, significantly alleviating pain, fatigue, and depression while enhancing mental health, overall psychological well-being, and physical functionality (13,27,28,42,43). Personalized exercise plans, adapted to individual needs and integrating both aerobic and strength training, prove most effective for individuals with FM (43,44). Additionally, combining PNE with MI and incorporating physical exercises targeting cognitive and emotional aspects facilitate a holistic shift in lifestyle and pain-related perceptions (2,17,26). This comprehensive approach allows participants to tangibly experience and validate concepts discussed, moving beyond verbal instruction and theory.

Throughout the FIBROWALK program, the rationale behind exercising is explained and motivation to encourage participation is provided through health education and risk appraisals (45,46). In each session, the participants are reminded of the significance of daily exercise and how staying inactive can exacerbate symptoms. Confrontation, as a strategy involving challenging or testing an individual’s beliefs, thoughts, or behaviours to promote changes, can also be useful in achieving this goal, as detailed in the CBT section.

To ensure a safe exercise progression, physiotherapists tailor the initial exercise level, the duration and intensity are adjusted according to each person’s needs and the program adheres to a maximum time limit.

Throughout the 12-week program, exercises gradually become more demanding in duration and complexity, employing a time-contingent strategy (47) to prevent pain escalation without physical harm. The evolving complexity involves not just higher intensity but also incorporates cognitive or emotional elements, like mindfulness practices combined with problem-solving or focused breathing. This integration requires heightened concentration and multitasking, merging physical activities with simultaneous cognitive or emotional involvement, such as responding to prompts during exercises or participating in collective storytelling.

The exercises are crafted to be engaging, prioritizing movement without fixation on pain, aiming to alleviate kinesiophobia, fear-driven behaviours, and enhance functional ability without heightening fatigue perception. Within the group, individuals gain confidence in performing various daily activities through gradual exposure and diminishing fear of movement.

In order to prevent nocebo effects, it is crucial to understand that group therapy does not entail sharing personal medical details among participants. Instead, it is a space for interaction with therapists and peers to address doubts or concerns. The emphasis lies in fostering a supportive, safe environment that encourages open communication during therapy sessions for all involved.

Physical exercises target enhancing overall body movement, fostering independence and confidence in everyday tasks. Incremental exposure during daily activities is pivotal. The program seeks to integrate learned strategies into daily life, with pain reduction as a secondary objective. Employing various strategies, it emphasizes an authentic lifestyle shift, urging individuals to actively engage in their recovery by addressing psychosocial elements that impact their well-being. CBT reinforces this aspect to target these elements.

Considering all the aforementioned factors, the therapeutic physical exercise program spans across all sessions (excluding the final one involving families), lasting for 40 minutes each. It progressively elevates in difficulty and duration, adhering to American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines (48). This regimen encompasses three segments: (1) a 5-minute warm-up, comprising activation and mobility exercises; (2) a 25-minute core exercise phase that blends moderate aerobic-cardiovascular and muscle strengthening routines, accompanied by engaging balance, coordination, and multitasking exercises with cognitive and emotional targets; (3) concluding with a 10-minute cool-down, integrating flexibility and relaxation exercises.

In addition to the sessions, the physical activity program incorporates homework, providing personalized walking guidelines to each participant. These guidelines establish a baseline and progression plan for the entire 12-week program. This systematic approach aims to enhance endurance and consistently challenges the participants.

While walking is usually recommended as homework, individuals have the option to choose a different aerobic exercise. Progression is customized based on personal preferences and capabilities. Advancement considers two aspects: (a) initially, prescribed aerobic exercise (primarily walking) is suggested once a week in the first month, twice a week in the second, and thrice a week in the third; and (b) an individualized exercise plan aligns with the person’s abilities and their current phase of change (49). This plan factors in cognitive, emotional, and evaluative processes, incorporating ten different change strategies. The Transtheoretical Model of Change by Prochaska and DiClemente (49) outlines stages of change (Precontemplation, Contemplation, Action, Maintenance) and associated strategies like self-efficacy, coping skills, and social support. It emphasizes a progression through stages, addressing barriers and utilizing support systems to sustain behavioural changes. The less advanced an individual is in the precontemplation phase, the more gradual the progression should be (refer to Appendix 4 for more details).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

CBT, a psychological approach, aims to adapt thoughts for improved emotions and actions (41). In FIBROWALK, CBT aligns with PSE principles, employing two primary methods. Firstly, therapeutic physical exercise challenges pain-related beliefs (39,50), addressing fear-avoidance behaviours outlined in the fear-avoidance model (50). The program does not primarily focus on pain reduction but on integrating physical activity into daily life. Confrontation is key, helping individuals understand that avoiding activity due to fear can decrease functionality, fuelling a cycle of increased fear and avoidance. Erroneous pain beliefs and catastrophic thoughts are addressed through CBT, therapeutic exercises, and PSE, fostering behavioural change.

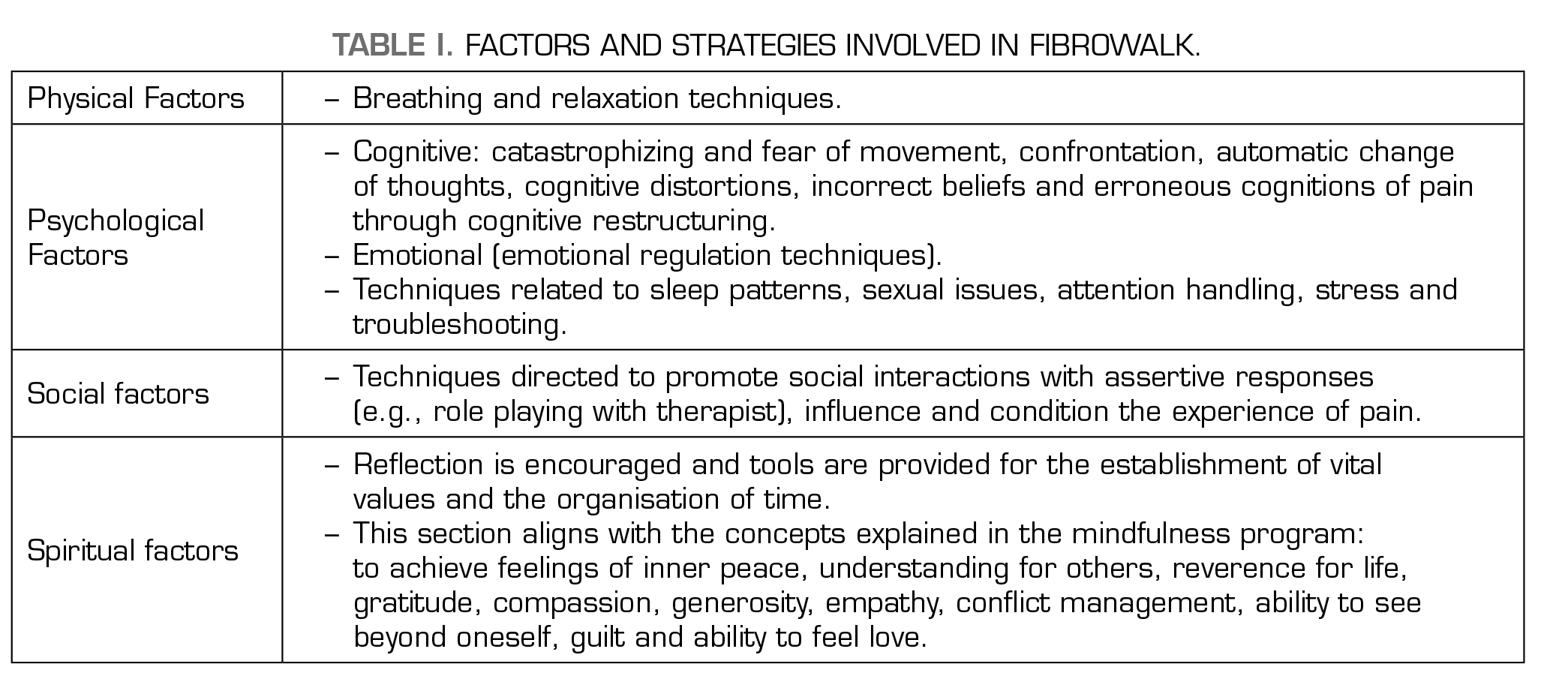

Secondly, FIBROWALK adopts a biopsychospiritual model, considering various factors and strategies summarized in Table 1.

Mindfulness training

In FIBROWALK, we propose integrating CBT with mindfulness training. Mindfulness, often defined as the conscious awareness cultivated by “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” is central to our approach (51). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) was originally developed to aid those experiencing chronic pain and high stress levels (51). Its core practices encompass sitting meditation, walking meditation, yoga, and the body scan—a technique guiding attention through various body parts. The ultimate goal of MBSR is to integrate mindfulness into daily routines. Recent systematic reviews highlight its efficacy in reducing anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, coping and stress perception in patients with fibromyalgia (52). Moreover, studies suggest that combining CBT with mindfulness interventions in FM may lead to decreased pain and depression, improved sleep quality, enhanced functional ability, and better overall work performance (53).

To support learning and home practice, we utilized the MBSR 8-week program (51). Our in-session training involves teachings from this program, supplemented by additional resources such as videos and readings available online through an MBSR-based platform (e.g., Palouse Mindfulness, https://palousemindfulness.com). The program’s weekly content is thoroughly explained during sessions and can be reinforced through assigned homework tasks (Appendix 2).

Homework in FIBROWALK

The homework assignments are a crucial part of FIBROWALK. They encompass both tasks to be done and responding to weekly questionnaires, which aid in monitoring the participants’ learning and also help consolidate their own understanding. Through homework, participants can delve into concepts that are not fully understood during the review phase at the beginning of each session, in which the therapist keeps track of the people who have completed their homework.

Homework is divided into two blocks:

Improving Adherence to FIBROWALK

We consider the following aspects pivotal for enhancing adherence:

Formats of FIBROWALK Adapted to Different Settings

FIBROWALK is a program with all its components specifically adapted to be taught in groups. The FIBROWALK program has been applied in a hospital context (24), in an outdoor context (54), and an online format (55). Groups are usually conducted with 20 participants, which can be considered relatively large. According to our clinical experience, large groups are more heterogeneous than smaller ones, and it is more difficult to respect each participant’s time to ensure that they assimilate the contents properly. However, we do not consider group size to be a substantial barrier. Despite being large groups, providing individual advice and reinforcement at each session is possible, mainly if more than one therapist is involved in managing the program. Moreover, the group can be a powerful strategic tool to achieve more treatment adherence and also heterogeneity may provide more diverse personal experiences which in turn may enrich dialogue and provide first-person examples regarding how to apply programme learnings into daily-life (56). FIBROWALK has been run so far by one psychologist and one physiotherapist, or by a unique person having both degrees, psychology and physiotherapy (which is unusual in clinical practice), but the comparisons of theses outcomes with other professionals are currently unavailable.

Due to the positive effects of exposure to outdoor natural settings (54) for physical and mental health, we recommend running FIBROWALK in a natural environment if possible. However, as it has been said, it can be done in a hospital or clinic (24) and in an online format (55). Other contexts and means of delivering FIBROWALK, such as conducted in-person associations spaces out of the hospital or in Virtual Reality settings, have not been explored yet but may even favour the number of people benefiting from the intervention. Still, further study is required to answer these research questions

THE FIBROWALK FIDELITY MEASURE

About FIBROWALK

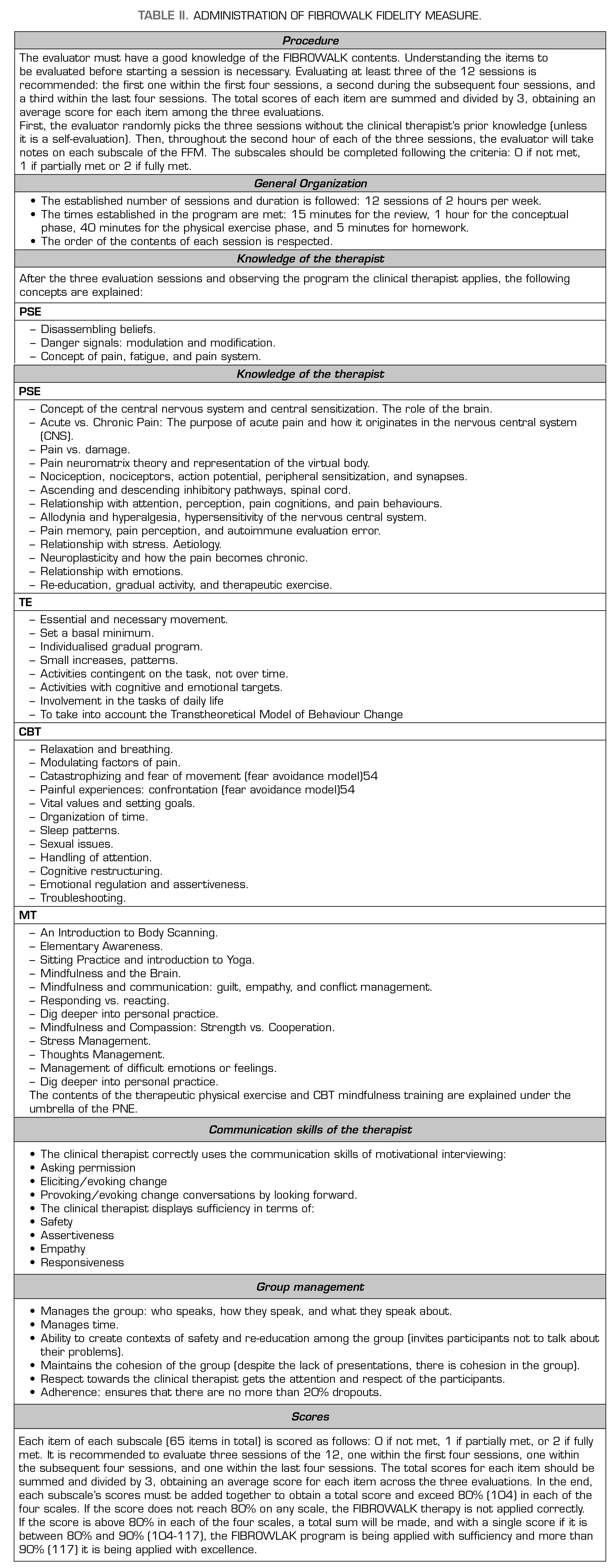

The FIBROWALK Fidelity Measure (FMF) is a valuable tool designed for clinicians and researchers implementing the FIBROWALK program in their clinical practice or research endeavours (see Table 2 Administration of FIBROWALK Fidelity Measure). Its purpose is to assess the fidelity of therapists in adhering to the program’s principles, protocols, and prescribed methods. By ensuring faithful implementation, the FMF serves as a critical means to guarantee the program’s integrity.

For clinicians integrating FIBROWALK into their practice, the FMF acts as a self-assessment tool. It allows them to gauge their adherence to the program’s components, ensuring they deliver the intervention as intended. Through this self-assessment, clinicians can identify strengths and areas for improvement in implementing the FIBROWALK program. The key areas evaluated by the FMF encompass general organization, therapist knowledge, communication skills, and group management. Each item within these categories should be scored on a 3-point scale: 0 for not met, 1 for partially met, and 2 for fully met.

Conceptual clarifications

General Organization

FIBROWALK consists of four basic components (i.e., PSE, therapeutic physical exercise, cognitive behavioural therapy, and mindfulness training) with a specific sequencing and timing for each component. It is important to respect the dosage of each component and its distribution over time.

Therapist Knowledge

The therapists delivering the program must have theoretical knowledge of the components of FIBROWALK (which can be performed by one or more clinical therapists). The therapists should also be familiarised with the concepts of each program component. In addition, therapists should have a deep knowledge of FM and its consequences and repercussions in the individual’s context in order to establish assertive and constructive communication with the affected persons.

Communication skills of the therapist

Using MI strategies is essential for successfully implementing the FIBROWALK program. What is said is as important as how the clinician says and expresses it.

Group management

The FIBROWALK program has been devised and verified for application in care settings with sizable FM participant groups (20 to 25 individuals per group). While it can be adapted for individual use, the collective environment plays a vital role in therapy. Yet, it’s crucial to distinguish it from psychotherapy or serving as a space for communication and emotional relief. Implementing validation strategies is essential to establish secure contexts that facilitate continuous re-education throughout the program’s duration.

DISCUSSION

Multidisciplinary approaches combining physical activity, psychological therapy, and psychoeducation have been employed in various contexts for managing FM and other chronic pain conditions (24,57,58). In general terms, these share elements in common with FIBROWALK, focusing on using physical and psychological strategies to improve overall health outcomes in people with fibromyalgia (59-61). However, in our program, we articulate contents using PNE as a framework, one of the few available treatments scientifically tested in our country. The program has been well accepted in the healthcare system and is currently being implemented in several clinical settings in the Barcelona area (Spain), including Taulí Hospital and other primary care centers. Preliminary data in all published papers indicate improvements in pain management and fatigue reduction. For example, a study conducted by Serrat et al. (2021) demonstrated significant reductions in symptom severity and improvements in quality of life after 12 weeks of participation in FIBROWALK.

However, certain limitations should be considered. Long-term adherence to the program remains a challenge for some participants, as does the need for tailored adaptations based on individual health status. Additionally, while the initial results are promising, larger-scale studies are necessary to validate its generalizability and further explore its long-term efficacy across different populations. The availability of trained professionals to deliver the program and access to adequate resources in diverse healthcare settings may also hinder its widespread adoption. Furthermore, there is a lack of studies with long-term follow-ups and studies involving different therapists. In this context, the On&Out study (Serrat et al., 2022), which aims to evaluate the long-term effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and immune-inflammatory mechanisms behind the program, is expected to address these limitations. The study results are anticipated to be published in the coming months.

Finally, it is also worth mentioning that the team is working on facilitating access to the program, taking into account the advantages of using Information and Communication Technologies. In this vein, FIBROWALK was offered as a distance program using videos during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results were quite positive (55), and for this reason, this modality of treatment is still offered to people in need, and we are working on new developments to facilitate access even more.

CONCLUSION

The FIBROWALK program represents a promising multicomponent approach to managing FM, integrating physical activity, mindfulness, CBT, and PNE. Initial data from clinical settings have demonstrated positive outcomes, including significant reductions in pain and fatigue and improvements in psychological well-being. The findings from Serrat et al. (2021) further support these benefits, highlighting significant symptom relief and enhanced quality of life over a 12-week period (24). Considering these results, it is worth continuing to study the long-term effects, ways to personalize the program, and exploring how to expand the benefits to as many people as possible.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept/idea/research design: M. Serrat

Writing: M. Serrat, E. Royuela-Colomer, A. Feliu-Soler

Data collection: M. Serrat

Data analysis: M. Serrat

Project management: M. Serrat, A. Feliu-Soler

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): M. Serrat, E. Royuela-Colomer, J. Nijs, X. Borràs, J.V. Luciano, R. Nieto, A. Feliu-Soler

FUNDING

The Vall d’Hebron Institute of Research funded this research. The project has been funded in part by the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation (MCIN) State R + D + I Program Oriented to the Challenges of Society- MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033- (ref. PID 2020-117667RA-I00) and co-financed with European Union ERDF funds. The last author (AF-S) acknowledges the funding from the Serra Húnter program (Generalitat de Catalunya; reference number UAB-LE-8015). The funding sources did not influence the study’s design, data collection, analysis, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

DISCLOSURES

JN and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel received lecturing/teaching fees from various professional associations and educational organizations. JN authored a book on pain science education, but the royalties are collected by the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium.

The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

REFERENCES