DOI: 10.20986/resed.2017.3661/2018

ORIGINAL

ADAPTA project: adequacy of treatment in breakthrough cancer pain

C. Álamo1, L. Cabezón-Gutierrez2 y grupo de trabajo del Proyecto ADAPTA*

*ADAPTA Project Working Group: G. Carrera Domenech, M. Múgica Estébanez, A. Moreno Paul, P. Garrido Valtierra, A. Yubero Esteban, V. Alcolea Fuster, A. Cotes Sanchís, R. Lara López, C. Molins Palau, A. M. Jiménez Gordo, E. Vicente Rubio, L. Iglesias Rey, R. Molina Villaverde, M. Lázaro Quintela, A. García Velasco, F. Gálvez Montosa, A. Marisol Sánchez, M. Corral Subias, E. Elez Fernández, A. L. Irigoyen Medina, M. Alsina Maqueda, A. Gómez Rueda, C. Álvarez Fernández, R. Sánchez-Escribano Marcuende, M. Sereno, B. Rodríguez Alonso, A. C. Virgili Maqueda, C. Delgado Fernández, A. Barba Joaquín, O. Higuera Gómez, J. L. Sánchez Sánchez, T. Fernández Rodríguez, M. Gil Martin, R. A. Albino Pérez, J. Muñoz Luengo, R. Afonso Gómez, M. L. Soriano Tabares de Nava, M. Dorta Suarez, L. M. Rodríguez Rodríguez, M. Selvi Miralles, A. Rodríguez-Vida, A. I. León Carbonero, I. Morilla Ruíz, C. Salguero Núñez, L. Heras López, V. Amezcua Hernández, J. David Cárdenas, G. Soler González, M. González de la Peña Bohorquez, M. Arruti, M. Mangas, F. Molano Criollo, S. Saura Grau, L. Layos Romero, G. Benítez López, L. Díaz Paniagua, J. García Sánchez, A. López Jiménez, V. Alonso, E. Aguirre Ortega, A. González Vicente, M. C. Cañabate Arias, F. J. Vázquez Mazón, M. T. Quintanar Verduguez, V. Zenzola de Toma, G. Pulido Cortijo, A. V. Correa Noguera, R. V. Salgado Ascencio, M. Marín Vera, A. Manzano Fernández, J. M. Martínez Lozano, N. Mohedano, R. Luque Caro, N. Luque Caro, I. Ramos García, J. M. Gasent Blesa, R. Monfort García, P. Martín Tercero, A. Calles Blanco, A. Soria Rivas, P. Zamora, M. F. García Casabal, D. Rodríguez Rubí, L. Vázquez Tuñas, I. Lorenzo Lorenzo, J. García Gómez, J. M. Vicent Vergé, M. D. Torregrosa Maicas, L. D. Condory Farfán, J. Cristóbal, J. Pérez de Olaguer, J. Coves Sarto, I. González Maeso, M. Soria, M. Benavent, R. Morales Barrera, A. Albert Balaguer, J. Garde Noguera, G. Bruixola, M. J. Gómez Reina, J. A. Contreras Ibáñez, M. Serrano Moyano, A. Vacas Rama, A. Moreno Vega, E. Díaz Peña.

Received: 24-01-2018

Accepted: 25-04-2018

Correspondence: Cecilio Álamo

cecilioalamo@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Transmucosal fentanyl has specific properties which make it ideal for the treatment of breakthrough cancer pain (BTCP). Although there is a broad consensus for the administration of transmucosal fentanyl for BTCP in Spain, there is uncertainty as to the way oncologists adjust their prescription to the patient and what are the determinants of the choice of different pharmaceutical forms.

Objectives: The main objective of this study was to analyze and prioritize the attributes that Spanish oncologists consider when assessing treatment options with transmucosal fentanyl in patients with BTCP.

Methods: A Scientific Committee performed a classification of 14 relevant attributes in the prescription of transmucosal fentanyl for BTCP. Subsequently, a dossier of scientific evidence was generated comparing these 14 attributes among the different available transmucosal fentanyl formulations, which was shared with the panel of experts (115 Medical Oncologists). After a thorough review of the document, the participants carried out an online vote for the prioritization of the attributes.

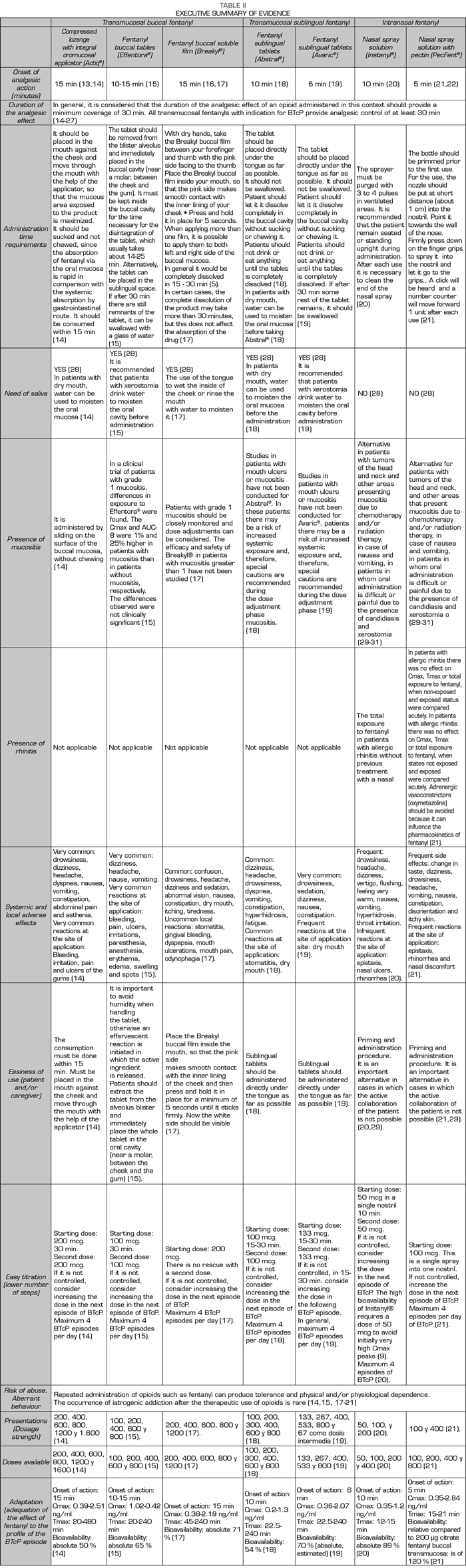

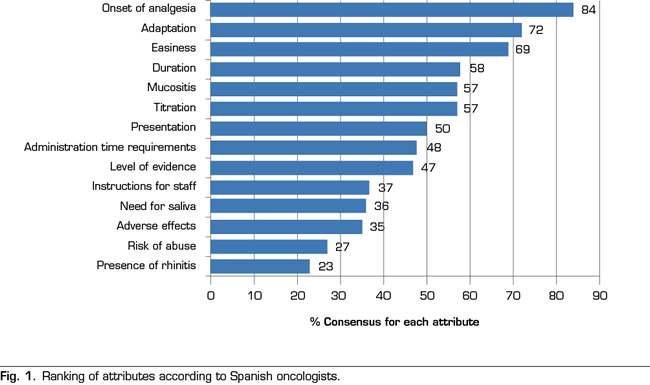

Results: Out of fourteen attributes analyzed, seven achieved a consensus of ≥ 50 % of the participants: the start of the analgesic action (84 %), the adequacy of the effect of fentanyl to the BTCP episode (72 %), the ease of use (58 %), the presence of mucositis (57 %),

the ease of titration of the optimal dose (57%), and the variety of presentations and doses available (59 %).

Conclusions: The most valued attributes were those related to the speed of action of the analgesic treatment and its adaptation to the BTCP profile, something to be expected given the spontaneous, unpredictable, and transitory nature of BTCP. As less valued attributes appear the risk of abuse or aberrant behavior and the presence of rhinitis for its administration, which indicates that the existence of these factors do not influence the choice of treatment for BTCP. These results will allow medical oncologists to know what attributes should be taken into account when customizing the patient's treatment of BTCP in order to improve the adequacy of rescue analgesia.

Key words: Breakthrough cancer pain, opioids, fentanyl, cancer pain management.

RESUMEN

Introducción: El fentanilo de administración transmucosa tiene características específicas que lo convierten en el fármaco adecuado para el tratamiento del dolor irruptivo oncológico (DIO). Aunque en España existe un amplio consenso sobre la idoneidad de la administración de fentanilo transmucoso para el DIO, es relevante conocer cómo los oncólogos adecuan su prescripción al paciente y cuáles son los factores determinantes de la elección de las diferentes formas farmacéuticas.

Objetivos: El objetivo principal de este proyecto fue identificar y priorizar los atributos que los oncólogos médicos españoles tienen en cuenta cuando valoran las opciones de tratamiento con fentanilo transmucoso en pacientes con DIO.

Métodos: Un comité científico realizó una tipificación de 14 atributos relevantes en la prescripción de fentanilo

transmucoso para el DIO. Posteriormente se generó un dossier de evidencia científica comparando estos 14 atributos entre los distintos fentanilos transmucosos disponibles, que se compartió con el panel de expertos (115 oncólogos médicos). Tras una exhaustiva revisión del documento, los participantes realizaron una votación online de priorización de los atributos.

Resultados: De catorce atributos analizados, siete consiguieron un consenso de ≥ 50 % de los participantes: el inicio de la acción analgésica (84 %), la adecuación del efecto del fentanilo al perfil del episodio de DIO (72 %), la facilidad de uso por los pacientes y cuidadores (69 %), la duración del efecto (58 %), la presencia de mucositis (57 %),

la facilidad de titulación de la dosis óptima (57 %) y las presentaciones y dosis disponibles (59 %).

Conclusiones: Los atributos más valorados fueron los relativos a la rapidez de acción del tratamiento analgésico y su adaptación al perfil del DIO, algo esperable dadas las características clínicas del episodio de DIO. Como atributos menos valorados aparecen el riesgo de abuso o conductas aberrantes y la presencia de rinitis para su administración, lo que indica que la existencia de estos factores no tiene tanta influencia en la elección del tratamiento para el abordaje del DIO. Estos resultados permitirán a los oncólogos médicos conocer qué atributos deben ser tenidos en cuenta a la hora de personalizar los tratamientos del paciente con DIO con el objetivo de mejorar la adecuación de la analgesia de rescate.

Palabras clave: Cáncer, dolor crónico oncológico, factores de riesgo, catastrofismo, método Delphi.

INTRODUCTION

Breakthrough pain is defined as a transient exacerbation of pain occurring spontaneously or in relation to a specific trigger, predictable or unpredictable, despite stable and adequately controlled baseline pain (1). Although breakthrough pain may occur in the context of several baseline pains (2), it has been better characterized in the oncology field. Breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP) can appear as a direct consequence of the tumor (70-80% of all cases), as a result of cancer therapy (10-20% of patients) or unrelated to the tumor or treatment (<10% of all cases) (3). The specific trigger factors of the BTcP can be identified in about half of the cases (4).

In 2013, a group of Spanish experts including specialists in Medical Oncology, Radiation Oncology, Pain Treatment Units and Palliative Care Units adopted a consensus document on the diagnosis and treatment of BTcP, which they defined as “an acute exacerbation of pain of rapid onset, short duration and of moderate to high intensity, that the patient suffers when he/she presents a stable baseline pain and controlled with opioids” (5). According to this consensus document, the ideal drug for the treatment of BTcP should meet the following specifications: a) be a powerful analgesic; b) have a rapid onset of action of 10 minutes or less; c) have a short duration of the effect (2 hours or less); d) have minimal side effects; and e) be easy to administer (easy, non-invasive and self-administered) (5). These attributes have been described in other studies by both Spanish oncologists (6) and foreign oncologists (7,8), and the consensus document has been adopted by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM), the Spanish Society of Radiation Oncology (SEOR), the Spanish Society of Palliative Care (SECPAL) and the Spanish Society of Pain (SED).

The various formulations of transmucosal fentanyl, for both buccal or nasal administration, have been a worthnoting improvement available to the physician for the therapy of breakthrough pain in cancer patients (9). These formulations have improved the efficacy and rapidity of action of classical opioids, including morphine, and their tolerability by patients is equivalent. Thus, the aforementioned consensus document indicates that “currently fentanyl is the active principle that best suits the analgesic needs of breakthrough pain due to its high analgesic potency and high lipophilicity, regardless of the major opioid used for the control of baseline pain” (5).

In 2010, the Declaration of Montreal proposed at the International Pain Summit recognized access to pain management as “a fundamental human right” (10). However, the prevalence of BTcP has been estimated that can reach up to 95% depending on the type of cancer and the diagnostic criteria, and about 60-90% of cancer patients die with pain (11). In Spain, considering that the prevalence of pain is very high in advanced stages of cancer (70-90%), it is estimated that at least 75,000 people face pain caused by cancer each year, with pain being the most feared symptom among these patients (12).

Clearly, the definition of BTcP, its diagnosis, assessment and monitoring can influence the choice of a treatment and, consequently, the patient’s outcomes. Therefore, reaching a consensus on these issues among a wide group of experts in this type of pain is important. The objectives of this study was, on the one hand, to review the available evidence to analyze and differentiate the attributes that oncologists consider to evaluate treatment options with transmucosal fentanyl in patients with BTcP. On the other hand, the objective was also to prioritize and generate recommendations on what attributes should be taken into account when customizing patient’s treatments with BTcP in order to improve the adequacy of rescue analgesia.

METHODS

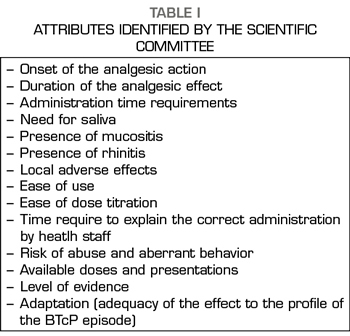

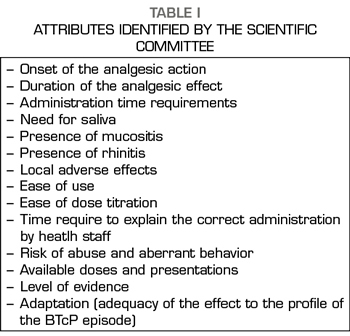

This project was conducted between May 21 and June 20, 2017 through the use of an online participatory tool. This collective intelligence tool was developed in three steps. In the first phase, a Scientific Committee comprised of Dr. Luis Cabezón Gutiérrez (Medical Oncology Service, University Hospital of Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid) and Dr. Cecilio Álamo González (Department of Pharmacology, University of Alcalá, Madrid) drafted a list of 14 attributes relevant to the prescription of transmucosal fentanyl for the BTcP (Table I). During the second phase, a review of the available evidence based on technical data sheets and literature was coducted to analyze and differentiate these attributes among the different available transmucosal fentanyls. Then, a complete Dossier of Evidence and an executive summary (Table II) were generated and shared, via electronic mail, with 115 medical oncologists from all over Spain. After the review of the dossier, the third and final phase began, the experts voted online through an online application for the prioritization of the 14 attributes.

RESULTS

The key question “What attributes do you consider most important when prescribing a treatment with transmucosal fentanyl for BTcP?” was asked to 115 oncologists. A total of 105 complete answers were obtained (94% participation).

Figure 1 shows the ranking of attributes obtained after the analysis of the voting. A total of 7 attributes out of the 14 established attributes obtained a majority of ≥ 50% of the participants: the onset of the analgesic action (84%), the adequacy of the effect of fentanyl on the profile of the BTcP episode (72%), ease of use (69%), duration of the analgesic effect (58%), presence of mucositis (57%), ease of dose titration (57%), and the availability of doses and presentations (50%). In contrast, the three attributes that had less relevance when prescribing a transmucosal fentanyl for BTcP were: the possible occurrence of adverse effects (35%), the risk of abuse or aberrant behavior (27%) and the presence of rhinitis (23 %).

DISCUSSION

The attribute reaching the highest level of consensus (84% of the participants) was the “onset of the analgesic action”. The rapidity with which the decrease or disappearance of pain due to therapy occurs is a primary requirement in the management of spontaneous or incidental breakthrough pain in the cancer patient. In this sense, despite the average time of onset of an episode of breakthrough pain is 2 to 3 minutes, the pain may last up to 1 hour, although approximately 73% of the episodes last less than 30 minutes. Among the currently available fentanyl formulations, fentanyl pectin intranasal spray provides the fastest onset of analgesia: 5 minutes after administration (25). Transmucosal fentanyls of buccal or sublingual administration have longer analgesic times, reaching in some cases even 15 minutes (11). In contrast, oral forms of immediate release of morphine or oxycodone show their analgesic effect approximately 30-40 minutes after oral administration, being clearly insufficient to adequately control the BTcP. Despite this, a recent survey showed that oral forms these are still widely administered (up to 98% of patients) in some northern European countries (32). A study conducted in 1000 cancer patients in 13 European countries showed that only 19% of patients received transmucosal fentanyl for the treatment of BTcP (33).

In an exploratory Delphi study conducted in Spain (6), the vast majority of respondents (97.8%) indicated that the ideal time for the onset of the analgesic effect should be a maximum of 15 minutes and the “onset of analgesic action” received a score of 6.5 in a scale of 1-7, in which 7 was “extremely important” (6).

The second attribute, with a level of consensus of 72%, was the “adequacy of the effect of fentanyl to the profile of the BTcP episode”. In this sense, the ideal drug for the treatment of BTcP should be a potent analgesic that can alleviate the high pain intensity. Given the pain transience, it should be a rapid absorption drug with rapid onset of action, its route of administration should be simple, easy and with high patients’ acceptance. This drug should not add additional side effects to the baseline treatment with opioids and the duration of the effect should not exceed 120 minutes. The new rapid-acting fentanyl formulations adapt to the profile of breakthrough pain and provide better efficacy and less toxicity (9). The number of episodes per day, the need to repeat the dose due to insufficient relief, and the degree of relief are important aspects that should be considered when titrating the medication to control the BTcP. (6). Some authors have proposed the establishment of doses that are proportional to baseline opioid regimens for baseline pain, because this seems to be effective and safe in most patients (34). In any case, the different aspects related to the ease of dose titration, the clinical characteristics of each patient and the patient’s need for social support are critical when choosing the treatment with fentanyl (6).

The third attribute, with a level of consensus of 69% of participants. was the “ease of use by the patient or the caregiver”. An added value when selecting a therapeutic option among different formulations is the simplicity of the administration device, which will facilitate patient’s adherence and compliance. The results of a survey conducted to Spanish oncologists showed that written instructions and information to the patient are often missing, a confirmation of whether the patient has understood the instructions and a systematic evaluation of pain (35). The study concluded that oncologists need to improve their communication skills, providing patients with written and verbal information about their illness and the plan for pain control (35). The intranasal formulation of fentanyl can be easily administered by a caregiver if the patient can not collaborate, avoiding the need for training if the patient is treated at home. In this sense, transmucosal fentanyl delivered via nasal has demonstrated to be in general faster than that administered buccally, since the nasal mucosa is more vascularized and more permeable (7).

The fourth attribute, with a level of consensus of 58%, was the “duration of the analgesic effect”. Breakthrough pain is a heterogeneous pain, with intra and interindividual variations. The episodes, even in the same subject, may have very different characteristics, which hamper their proper identification and assessment. The duration of analgesia was the second most important criterion for selecting a drug for BTcP in the above mentioned Delphi study of Spanish (6). A total of 74.1% of the respondents indicated that the duration of the analgesic effect should last a maximum of 1-2 hours (6).

The fifth attribute, with a level of consensus of 57%, was the “presence of mucositis”. The mucosa is an adequate route for the release of fast-acting drugs. However, the integrity of the mucosal epithelium, vascularization and hydration of the surfaces is important for the correct absorption of the different forms of buccal or sublingual transmucosal fentanyl. The presence of cancer processes in the oral cavity or alterations in the oral cavity as a side effect of certain treatments may interfere with the response to treatment. Patients receiving chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy may experience mucositis as a complication of such treatments. Pain related to mucositis hampers oral drugs delivery and leads to a decrease in fluid and food intake (36). Therefore, of course, this is an attribute that has a decisive influence when choosing a treatment with transmucosal fentanyl. However, a related attribute, the “need for saliva”, obtained only 36% of consensus among respondents (Figure 1).

The “administration time requirements”, or time that the applicator, tablet or film should remain in contact with the absorption surface in order to obtain the maximum absorption, did not reach a high consensus level (48% of the participants). It is possible that the participants assumed that the application is equally rapid for all the pharmaceutical forms of transmucosal fentanyl, or that this factor is not decisive for the speed of onset of analgesic effect.

The “level of scientific evidence” was not a main decisive attribute (47% of the participants). The studies that have rigorously addressed the comparison between the different options to establish which ones have a better risk-benefit balance are scarce (9). However, a Spanish survey published in 2010 showed that a high percentage of oncologists are unaware of some concepts of potential clinical importance, such as the actions of drugs on different opioid receptors (37). The consensus is clear regarding the administration of fast-acting fentanyl for the treatment of BTcP and Spanish oncologists see transmucosal fentanyl as an effective therapy. However, an effort to disseminate the technical aspects that would allow oncologists to know thoroughly the different therapeutic options seems to be a priority. In addition, despite the prevalence of BTcP and being a negative prognostic factor in cancer patients, the BTcP is underdiagnosed and poorly treated. A qualitative study conducted in Spain determined the adherence to the Clinical Guideline for the Treatment of Cancer Pain of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (38). This study showed that, despite unanimity (100%) regarding the need for specific treatment for the BTcP and in the use of fentanyl as the first-choice drug (99%) was found among oncologists (n = 83), the guideline suffers from a limited compliance, in part because of its low diffusion and in part because of the potential confusion regarding certain recommendations (39). Also, a study conducted with American oncologists showed that one of the barriers identified for the adequate treatment of pain was the need for specific training in this field (40). Despite transmucosal fentanyl is clearly perceived by Spanish oncologists as a safe and well tolerated therapy against BTcP, it is necessary to continue training healthcare staff at all levels.

The variety in the pharmaceutical forms of transmucosal fentanyl eases that each patient can be treated with the formulation that best suits his/her clinical characteristics and preferences. Therefore, the collaboration of trained health personnel is necessary to explain how to manage the BTcP. Even so, the attribute “time necessary to explain the correct administration of transmucosal fentanyl” only reached a 37% consensus among participating oncologists. However, nurses, pharmacists, caregivers and family members must be involved to ensure patient’s safety and to optimize the effectiveness of treatment.

It is notable that the occurrence of local adverse effects (related to the route of administration) in our analysis did not seem relevant when prescribing the different forms of transmucosal fentanyl (consensus of 35% of the participants). It is possible that oncologists are assuming that these forms of administration are equally safe and that adverse effects are common to all types of opioids (nausea, constipation, headache and sleepiness). It is also notorious that the participants in our study do not consider important the possibility of risk of aberrant behavior or abuse (27% of the participants). Finally, most oncologists do not considered the presence of rhinitis as a relevant attribute when prescribing medication, reaching this attribute only 23% consensus.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study regarding the priorities for prescribing transmucosal fentanyl for the treatment of BTcP showed that participating oncologists especially value the rapidity of the analgesic effect, the adequacy of the drug to the profile of the pain episode, the ease of use and the duration of the effect. These priorities are aligned with the needs of an effective treatment of the BTcP according to the consensus documents and currently available clinical practice guidelines. The low prioritization of attributes such as the possible occurrence of adverse effects, the risk of abuse, or the level of available scientific evidence stress the fact that Spanish oncologists perceive the different formulations of transmucosal fentanyl as safe, well tolerated, and effective drugs.

BIBLIOGRAPHY